(© Heleen Rodiers)

A virtuoso with a paintbrush, Stephan Balleux paints painting, making use as he does so of other disciplines such as sculpture, photography, and computer animation. At the Ixelles Museum – in his own borough – the exhibition “The Painting and Its Double” presents a panorama covering ten years of work by an artist who certainly doesn’t set out to make the viewer comfortable.

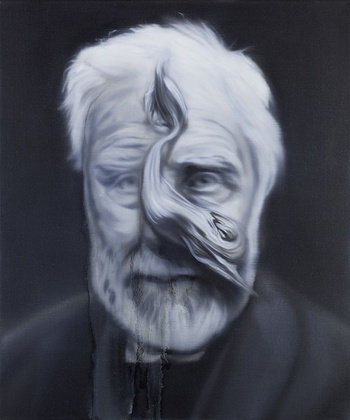

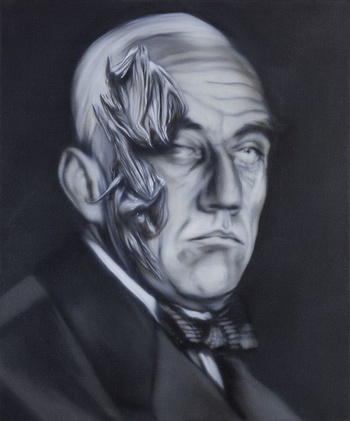

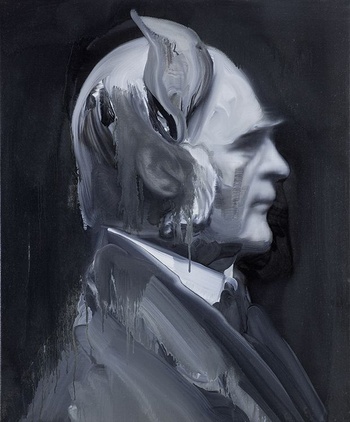

He calls it “the blob”, a reference to a cult 1958 horror film starring Steve McQueen in which viscous pink stuff of extraterrestrial origin devours the inhabitants of a small US town. Stephan Balleux’s own “blob” is a kind of painting that asserts its material nature, embedding itself in a reality as it swallows up faces and takes over space. “In my work, painting has become someone: it is a character, something organic to which I try to give a form.” Painting overruns painting and all our senses are unsettled as a result.

Stephan Balleux: swallowed by the blob

(The Third Gate, 2009)

Painting seems to be an obsession with you. Why did you choose the medium?

Stephan Balleux: In the course of my studies – I started off with evening classes at the age of ten and then went to the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles at the age of fourteen – I had the opportunity to do lots of different things. Sculpture, engraving, drawing, and photography, among others: but for me, painting was the most complicated. I didn’t understand much about painting, so that was where I had to explore. Painting is still a great enigma for me and that’s something I try to convey in my work. Painting is a medium that asserts right from the start that everything you see is fake. But for a very long time it relied on a kind of virtuosity that reproduces a certain reality. I find all those questions still very relevant today, even in this digital age with its continuous flow of images. As time went by, it became clear that what interests me is not making a painting, but the question of painting.

And yet, at the starting point of your paintings, there is always a photographic image.

Balleux: For a number of years, I was trying to get out of painting, while asking questions about painting all the time. The way out I found was to use other media to talk about pictorial questions. In my working process, I find an image in books that, taken out of its context, will be able to say something different. I tend to think that the work of collecting images and of theoretical consideration of images actually makes up 75% of my work. I like to use images that I haven’t made myself, because they speak of what is collective, of history, and of the society that produced them. I take an image, I photograph it, I reproduce it, often in miniature, I paint on it, I re-photograph it, I rework it using Photoshop, and then I paint it. There is never a photograph underneath my painting. It might seem very painstaking, but it isn’t at all. There are lots of things that I don’t paint: I just keep the strict minimum. In my way of painting, it’s not possible to reproduce identically. If I do a painting in black and white, I prepare a black, a white, and a grey and I mix the colours on the canvass. I improvise a lot on what turns up; I let the painting talk. That is one of the basic principles of painting: if you don’t listen to it, the result is not very vibrant. You have to let it happen.

Painting seems to be an obsession with you. Why did you choose the medium?

Stephan Balleux: In the course of my studies – I started off with evening classes at the age of ten and then went to the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles at the age of fourteen – I had the opportunity to do lots of different things. Sculpture, engraving, drawing, and photography, among others: but for me, painting was the most complicated. I didn’t understand much about painting, so that was where I had to explore. Painting is still a great enigma for me and that’s something I try to convey in my work. Painting is a medium that asserts right from the start that everything you see is fake. But for a very long time it relied on a kind of virtuosity that reproduces a certain reality. I find all those questions still very relevant today, even in this digital age with its continuous flow of images. As time went by, it became clear that what interests me is not making a painting, but the question of painting.

And yet, at the starting point of your paintings, there is always a photographic image.

Balleux: For a number of years, I was trying to get out of painting, while asking questions about painting all the time. The way out I found was to use other media to talk about pictorial questions. In my working process, I find an image in books that, taken out of its context, will be able to say something different. I tend to think that the work of collecting images and of theoretical consideration of images actually makes up 75% of my work. I like to use images that I haven’t made myself, because they speak of what is collective, of history, and of the society that produced them. I take an image, I photograph it, I reproduce it, often in miniature, I paint on it, I re-photograph it, I rework it using Photoshop, and then I paint it. There is never a photograph underneath my painting. It might seem very painstaking, but it isn’t at all. There are lots of things that I don’t paint: I just keep the strict minimum. In my way of painting, it’s not possible to reproduce identically. If I do a painting in black and white, I prepare a black, a white, and a grey and I mix the colours on the canvass. I improvise a lot on what turns up; I let the painting talk. That is one of the basic principles of painting: if you don’t listen to it, the result is not very vibrant. You have to let it happen.

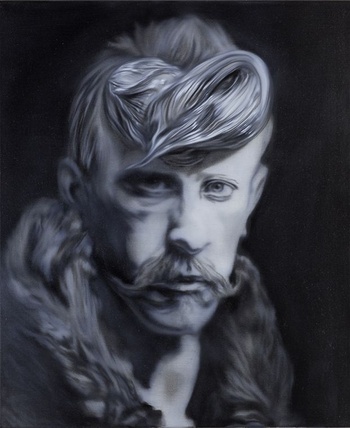

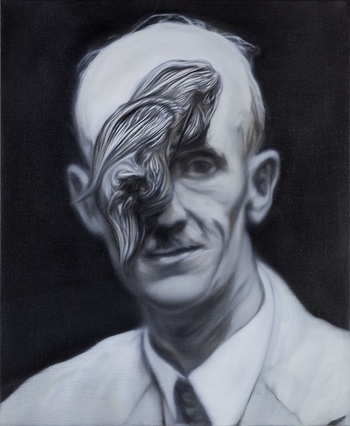

(Wanderlust series: George Grey / Fridtjof Nansen / William Beebe / Roald Amundsen / Francis Galton / Louise Boyd, 2010)

The images used are often in black and white and give the impression of being old.

Balleux: I like playing with different time frames. Working on images redolent of the 1950s, the 1920s, or even much earlier and mixing them: that creates a sort of imbroglio. It has a destabilising side to it, but a very familiar one too. That loss of bearings is something that I look for, in myself and in the people who look at my work. As for the black and white, there are various levels. Nothing is more abstract than black and white. But it is ambiguous, because people of my generation knew black-and-white photographs as one of the most ostentatious forms of reality. Black and white is at once extremely abstract and extremely real. It fascinates me when things are not obvious.

The images used are often in black and white and give the impression of being old.

Balleux: I like playing with different time frames. Working on images redolent of the 1950s, the 1920s, or even much earlier and mixing them: that creates a sort of imbroglio. It has a destabilising side to it, but a very familiar one too. That loss of bearings is something that I look for, in myself and in the people who look at my work. As for the black and white, there are various levels. Nothing is more abstract than black and white. But it is ambiguous, because people of my generation knew black-and-white photographs as one of the most ostentatious forms of reality. Black and white is at once extremely abstract and extremely real. It fascinates me when things are not obvious.

(© Heleen Rodiers)

Your works certainly don’t put the viewer in a position of comfort.

Balleux: I admit that my goal in my art is not to cheer people up. The idea is that it should affect them. I will always be more on the side of a Caravaggio than – and I know this will infuriate some people [Laughs] – of a Raphael. Raphael is beauty in its purest form: everything is where it should be; there isn’t the least fear or doubt. Francis Bacon’s paintings are often seen as being very aggressive, but I don’t perceive them that way. It is work that addresses the human condition and I have always felt myself to be on the same wavelength as it. I read a lot: philosophy, anthropology, the history of religion, etc. I always wonder about what human beings are doing on earth and that continues to feed into my work.

FOCUS ON A WORK: Hold Everything Dear (2010)

“It’s quite an emblematic work,” explains Stephan Balleux. “The starting point was a book, The Art of Memory by Frances A. Yates, which among other things deals with the mnemonic techniques employed by the Ancient Greeks. The rule is that to memorise a whole series of things in order, you have to place objects in an invented location. The more precise the imaginary place, the easier it is. What struck me above all was the interlocking of word and image. Following on from that, as someone who was more interested in portraiture and organic forms, I started to collect images of spaces. Abandoned spaces, at first, before I realised that there is more power in things that are totally banal.”

Your works certainly don’t put the viewer in a position of comfort.

Balleux: I admit that my goal in my art is not to cheer people up. The idea is that it should affect them. I will always be more on the side of a Caravaggio than – and I know this will infuriate some people [Laughs] – of a Raphael. Raphael is beauty in its purest form: everything is where it should be; there isn’t the least fear or doubt. Francis Bacon’s paintings are often seen as being very aggressive, but I don’t perceive them that way. It is work that addresses the human condition and I have always felt myself to be on the same wavelength as it. I read a lot: philosophy, anthropology, the history of religion, etc. I always wonder about what human beings are doing on earth and that continues to feed into my work.

FOCUS ON A WORK: Hold Everything Dear (2010)

“It’s quite an emblematic work,” explains Stephan Balleux. “The starting point was a book, The Art of Memory by Frances A. Yates, which among other things deals with the mnemonic techniques employed by the Ancient Greeks. The rule is that to memorise a whole series of things in order, you have to place objects in an invented location. The more precise the imaginary place, the easier it is. What struck me above all was the interlocking of word and image. Following on from that, as someone who was more interested in portraiture and organic forms, I started to collect images of spaces. Abandoned spaces, at first, before I realised that there is more power in things that are totally banal.”

“In a book on interior decoration, I found this image of a bed, which really got to me. There was something latent in that image and I decided the latent was going to be less latent. I copied and pasted my ‘blob’, the pictorial form that I wanted to be quite aggressive and threatening. I experimented a lot, with lots of different spaces. The only piece I made specially for the Ixelles exhibition came out of that too. On the basis of photographs of hotel interiors – there is nothing more familiar than a hotel and at the same time, it is completely impersonal and disembodied – I painted two canvases, 18 metres long and 2 metres 40 high, which are installed face to face, one reflecting the other. It’s at once a painting, a performance – I have to admit that I suffered a bit to paint them – and an installation and an architecture, as it’s a sort of large wall that changes the whole museum space. When you enter the exhibition, you find yourself in this panorama. Left and right, it’s the same thing, but at the same time, it’s not the same thing, as it has been painted. Always with this idea of unsettling the senses. But here there is no ‘blob’. The blob is the viewer.”

EXTRA: visit Stephan Balleux's Wunderkammer

STEPHAN BALLEUX: PAINTING AND ITS DOUBLE • 26/6 > 14/9, di/ma/Tu > zo/di/Su 9.30 > 17.00, €5/8, Museum van Elsene/Musée d’Ixelles, rue J. Van Volsemstraat 71, Elsene/Ixelles, 02-515.64.21, www.museumvanelsene.be, www.museedixelles.be

EXTRA: visit Stephan Balleux's Wunderkammer

STEPHAN BALLEUX: PAINTING AND ITS DOUBLE • 26/6 > 14/9, di/ma/Tu > zo/di/Su 9.30 > 17.00, €5/8, Museum van Elsene/Musée d’Ixelles, rue J. Van Volsemstraat 71, Elsene/Ixelles, 02-515.64.21, www.museumvanelsene.be, www.museedixelles.be

Read more about: Expo

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.