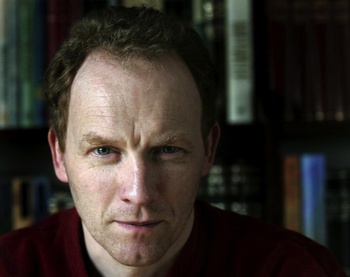

(© Einar Falur Ingolfssón)

Icelandic author Jón Kalman Stefánsson gave us both goose bumps and a warm, hearty glow with his impressive triptych Heaven and Hell, The Sorrow of Angels, and The Heart of Man. The perfect conditions to catch a winter flu.

Reading Jón Kalman Stefánsson gave me a cold. We imagine the Icelandic author couldn’t want for a better review. In his trilogy of novels – which comes in at just under 1,000 pages and is currently in film production – his characters have to deal with more than a trifling cold. The voracious reader Bárdur succumbs to death by poetry: fascinated by the verses of Milton’s Paradise Lost, he forgets to put on his coat when he goes out fishing, gets hypothermia, and dies. The death of his good friend is the starting shot of the physical war of attrition and the inner journey to maturity of the nameless boy who is the protagonist in Jón Kalman Stefánsson’s masterful triptych. A physical and emotional journey that forms the skeleton of a literary body of work that is far more than a mere Bildungsroman. Jón Kalman Stefánsson: “To me, writing a novel is not just telling a story, but also an exploration of language and an attempt to expand it in a way, trying to change the word ‘touch’ into a physical experience. I want the reader to feel the book in his/her bones. I know it’s an impossible feat, but aren’t poetry and fiction akin to the illogical and the impossible? You know, I’ve never written a book that I intended to write. When you’re writing, there’s always and constantly something unexpected popping up – a new character, an unforeseen turn in the story, words that you didn’t expect to rise up from the depths. I´m happy for that. Fiction and poetry are, in my opinion, part of the unforeseen and should therefore be impossible to structure beforehand. As an author you shouldn’t try to force your opinion onto literature, you should always obey its laws. If not, the novel will lose its power.”

One driving force in the narrative is the army of ghosts, hovering between life and death. This flock of troubled souls is thoroughly Icelandic, while at the same time connecting the rugged landscape and the hardship of 19th century island dwellers to the feelings and thoughts that pervade our time.

Jón Kalman Stefánsson: There is a verse in a famous Icelandic poem from 1946 that says: ‘You can never escape your hometown.’ Like it or not, you always bear the mark of your home. Icelandic history, nature, literature and language have shaped me. And we do have a rich heritage: the Icelandic sagas from the 13th century, that have influenced most of the Icelandic writers, whether they have read them or not. But at the same time, I have been influenced by foreign authors as well, by the history of mankind, and the breath of the universe. A novel can, at the same time, tell a story of the tiniest detail and embrace the whole world. That is, can be, or rather, should be the beauty of the modern novel.

To describe the Icelandic white-out in all its glory, you delve deep into language and dig up gems that would feel at home in the square centimetres of a poetry collection. When did you discover the power of combining poetry and fiction into such a sensuous, organic, living language?

Kalman Stefánsson: Well, actually I started out as a poet, publishing three books of poetry – the last one in 1993. Finding my voice as a writer of fiction was a struggle: I wrote two very bad novels – embarrassingly bad – but luckily I had the sense to throw them out. I finally found my path one gloomy day in January 1996, when the sky over Reykjavík was heavy with winter darkness. My head was just as dark as the sky: I was convinced that I would never be able to write a decent novel, and that I was finished as a poet. But I decided to write one last short story, about rather trivial things. I sat down, completely forgot about myself, and before I knew it, I had written a trilogy, which was published between 1996 and 1999. Everything went wide open for me at that moment, and I realised that there is almost no difference between fiction and poetry. You know, a contemporary writer is constantly struggling with all of those thousands and thousands of books already written, using words that are more or less worn out. Finding new ways of telling a story is not an easy task, but it’s a necessary one: if authors don’t challenge the form of the novel, it will die. My way to write was to breathe poetry through fiction. And I’ve kept on doing it ever since.

Jón Kalman Stefánsson: winter is coming

The whole trilogy is an allegorical defence of literature on shaky human legs. How important is literature to you, as a reader ánd as a writer?

Kalman Stefánsson: I have always read a lot, and with great eagerness. Literature has so much to offer, and its strength is that it sometimes exceeds our understanding. Something mysterious can happen when you put two words together, when you listen to that strange silence those two words create between themselves.

Literature is the only way for me to live. Without it I would wither. When I write, I always pour every cell, every drop of blood I have in my veins into my work. But good books are always better, bigger, deeper, wiser than their author. I simply can’t write without immersing myself in the characters, their life and death, without trying to change the world with every word.

Confronted with a world that is often hitting him hard, the nameless boy is subjected to doubts about the meaning of literature. Have you also experienced these doubts yourself?

Kalman Stefánsson: Yes, constantly! And they can be a burden. But then again, nothing is as vital to an author as doubts. To be too sure of oneself is the main danger for any artist. To doubt about the meaning of writing, the meaning of life, the quality of your work can be your best friend and ally, as difficult, heavy, and dark as that state of mind can be sometimes.

Those doubts and questions ultimately lead to exposing the world behind the world, according to the nameless boy, who seems to be very close to you as a writer. It seems like you found a definition of literature.

Kalman Stefánsson: That’s exactly what writing should be about: asking important questions! Literature should stir, move, and trouble readers, and at the same time, tell them something about the world and themselves. It should make, even force them to see their lives from a new perspective. It should fight against injustice, greed, it should open readers’ minds. Literature should matter.

JÓN KALMAN STEFÁNSSON • 6/2, 20.00, €5/7, EN, Passa Porta, rue A. Dansaertstraat 46, Brussel/Bruxelles, 02-226.04.54, www.passaporta.be

Kalman Stefánsson: I have always read a lot, and with great eagerness. Literature has so much to offer, and its strength is that it sometimes exceeds our understanding. Something mysterious can happen when you put two words together, when you listen to that strange silence those two words create between themselves.

Literature is the only way for me to live. Without it I would wither. When I write, I always pour every cell, every drop of blood I have in my veins into my work. But good books are always better, bigger, deeper, wiser than their author. I simply can’t write without immersing myself in the characters, their life and death, without trying to change the world with every word.

Confronted with a world that is often hitting him hard, the nameless boy is subjected to doubts about the meaning of literature. Have you also experienced these doubts yourself?

Kalman Stefánsson: Yes, constantly! And they can be a burden. But then again, nothing is as vital to an author as doubts. To be too sure of oneself is the main danger for any artist. To doubt about the meaning of writing, the meaning of life, the quality of your work can be your best friend and ally, as difficult, heavy, and dark as that state of mind can be sometimes.

Those doubts and questions ultimately lead to exposing the world behind the world, according to the nameless boy, who seems to be very close to you as a writer. It seems like you found a definition of literature.

Kalman Stefánsson: That’s exactly what writing should be about: asking important questions! Literature should stir, move, and trouble readers, and at the same time, tell them something about the world and themselves. It should make, even force them to see their lives from a new perspective. It should fight against injustice, greed, it should open readers’ minds. Literature should matter.

JÓN KALMAN STEFÁNSSON • 6/2, 20.00, €5/7, EN, Passa Porta, rue A. Dansaertstraat 46, Brussel/Bruxelles, 02-226.04.54, www.passaporta.be

Read more about: Expo

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.