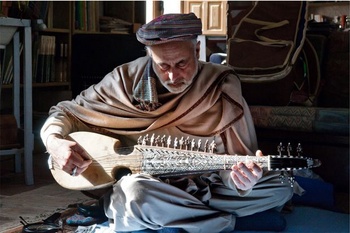

(© Javier Gonzáles)

One of the greatest figures of traditional Afghan music is coming to Muziekpublique in the context of the Notes of Freedom festival. Daud Khan is a master not just of the rubab, a traditional lute, but also of the sarod, an Indian string instrument. “I want to keep alive the age-old exchange between Afghan and Indian music.”

Daud Khan left Afghanistan 35 years ago because of his discontent with a regime that took away his freedom to experiment with his music. “As in music, you also have to be free to organise your own life,” Khan told us from his new home in Cologne in Germany. “After more than forty years of war, there is a deep yearning and nostalgia for peace and freedom in Afghanistan. For our country is very rich, especially in natural resources. We have a unique water supply system that has sustained a flourishing agriculture for centuries, even in the high mountains. Sadly, all that has been destroyed. But the traditional knowhow is still there; if we invest in it, we can grow organic crops and healthy food for the whole population. Hence the sheaves of wheat on the flag of Afghanistan.”

So there is hope for Afghanistan?

Daud Khan: Hope springs eternal! I would love to go back to my country, if there was peace. I want to open a cultural centre to accommodate my instruments and to give music lessons to young people. There is a real need for that: young people don’t play the rubab any more.

Even though it is an age-old instrument, representative of the Afghan tradition…

Khan: It is very important in folk, classical, and popular music. When I was young, there were lots of rubab-makers all over the country to meet the great demand. Now there is just one left, in Kabul. Which means the music is in danger of dying out.

Is that one of the consequences of the Taliban regime?

Khan: The focus on the Taliban is influenced by the media. First there was the devastation of our culture by the Communist invasion from Russia. Thousands of people died as a result. Before that the country was occupied by the British, who also wreaked cultural havoc. All those foreign powers occupied Afghanistan because of its strategic location. But in times of peace our culture flourished, especially between 1950 and 1962, with a king who was respected all over the country. He ensured national security and laid the foundations for a rich cultural life.

Daud Khan: standard-bearer of Afghan music

You also play the Indian sarod. How did that happen?

Khan: The instruments are similar. The right-hand playing is identical; the only difference is in the frets: the rubab has four, whereas the sarod has none, so you can do glissandos on it. I went to study the sarod in India in order to extend my knowledge of ragas [the framework for improvisation in Indian music - BT].

What is maybe even more important is the strong historical bond between India and Afghanistan, which is more than 2,000 years old. In the past, rubab-players were also traders who went to India to trade in goods. They always took their favourite instrument with them. There has never been a border between Afghan and Indian art and music. That artificial border was drawn by colonisers and foreign powers.

Daud Khan • 25/1, 20.00, €10, Muziekpublique/Théâtre Molière, Naamsepoortgalerij/galerie de la Porte de Namur, Bolwerksquare 3 square du Bastion, Elsene/Ixelles, 02-217.26.00, www.muziekpublique.be

Khan: The instruments are similar. The right-hand playing is identical; the only difference is in the frets: the rubab has four, whereas the sarod has none, so you can do glissandos on it. I went to study the sarod in India in order to extend my knowledge of ragas [the framework for improvisation in Indian music - BT].

What is maybe even more important is the strong historical bond between India and Afghanistan, which is more than 2,000 years old. In the past, rubab-players were also traders who went to India to trade in goods. They always took their favourite instrument with them. There has never been a border between Afghan and Indian art and music. That artificial border was drawn by colonisers and foreign powers.

Daud Khan • 25/1, 20.00, €10, Muziekpublique/Théâtre Molière, Naamsepoortgalerij/galerie de la Porte de Namur, Bolwerksquare 3 square du Bastion, Elsene/Ixelles, 02-217.26.00, www.muziekpublique.be

Read more about: Muziek

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.