One of the world’s most controversial photographers, Andres Serrano, comes to Brussels. His iconic Piss Christ was, like his work in mortuaries and with body fluids, never intended to provoke. “As a former drug addict, I have survived a few overdoses, so I didn’t understand the fuss about a few photographs,” says the artist who, after immortalising the homeless people of New York, has now done the same for their counterparts in Brussels.

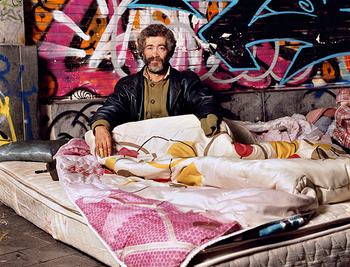

The “Uncensored Photographs” retrospective exhibition, which opens this week at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts, demonstrates once more the symbolic power of the work of Andres Serrano (who was born in New York in 1950). The US photographer confronts viewers with a raw reality, often with a religious touch or sexually charged, that others find it convenient to suppress. The exhibition also contains his photographs of Brussels homeless people in the city’s streets. They, too, tell us something about his empathic approach.

What was your first impression of the homeless people of Brussels?

Andres Serrano: There are a lot of them, and they are different from the homeless people I photographed in New York. Sometimes they seemed to be more like performers putting on some kind of act. I saw more women too, and even children. In New York, you don’t see children begging. It seemed too, that they had more stuff: with all their boxes, they could almost erect cardboard apartments in the metro or in the park.

Did you approach them differently than in New York?

Serrano: No. I explain to everyone what I want to do. In New York, I offered every homeless person I photographed 50 dollars, in Brussels 50 euro. They rarely said no. That is the way I always work. Whether it’s a homeless person or not, in return for posing, I always give a print or a little money.

Why did a project about homeless people appeal to you?

Serrano: I had photographed them before, 25 years ago, but that time against a neutral background. It was only when I was asked in 2014 to record them in their usual locations on the street that I realised there were far more of them than in the past. I found that disconcerting. Moreover, as in Brussels, it was for an art project in public space. In the West 4th Street subway station in Greenwich Village, all the pedestrians have to go through a long corridor that is full of maddening advertisements begging you to spend money on things you don’t need. My photographs of homeless people were a much better fit.

You claim that you don’t want to spread a message with your photography. “The best photographs are shrouded in mystery and contradiction,” you once said.

Serrano: You know, when a friend saw the long list of names hanging alongside the photographs of homeless people, he asked me: “Is that the list of sponsors?” Well, no, those were the names of the homeless people. That is the only extra explanation you’ll get from me. I’m not asking anyone to give them anything or even to feel anything. I’m not preaching. I just show what I see. The viewer interprets and draws his or her conclusions. That’s the way I always work.

Passers-by often don’t even deign to see homeless people. You do, and you give them a name.

Serrano: A photograph’s title functions as a guide for the viewer. If a photograph is completely red and you see the word “Blood” beside it, then you realise you are not looking at red paint. By giving the photographs of homeless people their own names, I allow them some dignity, even though some of them are trying to sleep or may be completely covered up by their sleeping bags. And the viewer realises that it is a collaboration with the homeless people.

In New York, you call them “residents”, in Brussels “denizens”. Why the difference?

Serrano: To make some kind of distinction. When I looked up the word “denizen”, I saw it was defined as a living being from a particular place: it could be a person, but it could also be an insect or a germ. I felt that that more surreal approach really did fit the homeless people in Brussels, the surreal city of Magritte. One man was shaking his knee the whole time, with his hand raised: a bizarre performance with a real feel for theatre, which I could only call surreal.

In the case of your most notorious photograph, Piss Christ, too, the title was important. Not intended to provoke, you said, but an accurate description of what you had photographed.

Serrano: It was Christ and it was piss. I never had any doubt what the title should be.

The fact that you call yourself a Christian added an extra layer of meaning.

Serrano: People sometimes ask me why I don’t do something about the Jewish faith or about some other religion. My answer is invariably: “But that’s not my religion.” I was born and raised a Catholic, so I believe that I have the right to use the symbols of the Catholic Church. I made Piss Christ from the inside, not from the outside.

Someone in the Vatican once said you were a transgressive artist, but not a blasphemous one. You must have been pleased to hear that.

Serrano: Yes, but I’m hoping for more. I hope to be received sometime by Pope Francis. I don’t just want the Catholic Church to recognise me, but also to give me a commission as a Christian artist. I want to be part of the long tradition of religious art that Caravaggio is also part of. Before the sixteenth century, religious art was the only kind that mattered; now it hardly matters at all. Well, Piss Christ is art and it is religious. It depicts a tortured man who, after being crucified, loses control of his bodily functions and fluids. If it upsets people, maybe that’s because I have brought a symbol closer to its original significance.

Your work is often not understood.

Serrano: Or deliberately misinterpreted. Misused too, often by right-wing forces. When Swedish neo-Nazis vandalised my sex photographs, I was shocked, but it was kind of weird: a group of people I thought had no interest in art, certainly not in my work, suddenly began to pay attention to it. [Ironically] And so Nazis have become art critics again.

In your retrospective there is a special focus on some works that were daubed or destroyed by opponents.

Serrano: It is a bold move, but the museum director, Michel Draguet, wanted to bring them together because censorship is still an important topic. I put all my cards on the table: I didn’t want to keep anything hidden.

It was only at the age of forty that you were able to make a living from your art. Were there advantages to that too?

Serrano: At the age of seventeen, I went to the Brooklyn Museum Art School, where I spent two years, but I soon realised that I couldn’t paint and I started to take photographs. But instead of becoming a photographer, I became a drug addict. That took a lot out of me. I survived a few overdoses and kicking the habit was really tough, but it did help me to cope with what happened to me later. With that heavy past, I didn’t understand the fuss about my photographs, but I was prepared for the controversy. Because of my earlier addiction, I also know what it’s like to be the goodie and the baddy, to be marginalised, and it is easier for me to identify with, for example, homeless people. Fortunately, I have always had a sense of destiny. Inspired by Marcel Duchamp and Picasso, I already wanted to be an artist at the age of fifteen. That dream could only come true once I was completely free of drugs and that finally saved me.

UNCENSORED PHOTOGRAPHS

18/3 > 21/8, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, www.fine-arts-museum.be

THE DENIZENS OF BRUSSELS

18/3 > 1/4, Brussels streets + Brussel-Congres/Bruxelles-Congrès (station), www.recyclart.be

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.