Anton Kannemeyer: Bitterkomix for a bitter world

With the exhibition “Don’t Shoot! We Are Not Armed!”, Recyclart is opening its doors to South African underground comics. And if you use the words "underground comics" and "South Africa" in the same sentence, chances are you're talking about Bitterkomix, the razor-sharp comic strip magazine founded in the early 1990s. We had the privilege to serve up some questions to founder and comics artist Anton Kannemeyer!

What was it that made you start with Bitterkomix?

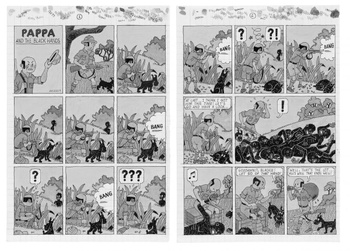

Anton Kannemeyer: I've had a huge interest in comics since I was a child. I always wanted to become a comics artist. But in South Africa there was no comic-reading culture, so I thought: "Let's see if I can make comics as a student" - and then maybe do something else when I have to deal with the "real" world. We studied illustration and that allowed me to do some comics as projects. The first stories dealt with conscription, so it started off dealing with socio-political issues right from the beginning.

The first issue was published in 1992, I believe. At that time, the abolishment of the Apartheid system was still ongoing. Was it a difficult time to get something like Bitterkomix off the ground? If so, did it get easier?

Kannemeyer: It was difficult. I was warned by some of my lecturers that we (me and Conrad Botes, who started the comics magazine with me) might get into trouble if the comic was seen by the "wrong" people. The most difficult thing from a practical perspective for us was to get funding for the publication. In the end we used scholarship money to pay for the first issue. It was money well spent in retrospect. Luckily, the press was very enthused about the magazine - we got very good reviews. At the time it was clear that we were heading for democracy in South Africa, and Bitterkomix was a new and challenging cultural product in a medium that was always considered to be conservative and for children. It certainly got easier as we progressed.

What was it that made you start with Bitterkomix?

Anton Kannemeyer: I've had a huge interest in comics since I was a child. I always wanted to become a comics artist. But in South Africa there was no comic-reading culture, so I thought: "Let's see if I can make comics as a student" - and then maybe do something else when I have to deal with the "real" world. We studied illustration and that allowed me to do some comics as projects. The first stories dealt with conscription, so it started off dealing with socio-political issues right from the beginning.

The first issue was published in 1992, I believe. At that time, the abolishment of the Apartheid system was still ongoing. Was it a difficult time to get something like Bitterkomix off the ground? If so, did it get easier?

Kannemeyer: It was difficult. I was warned by some of my lecturers that we (me and Conrad Botes, who started the comics magazine with me) might get into trouble if the comic was seen by the "wrong" people. The most difficult thing from a practical perspective for us was to get funding for the publication. In the end we used scholarship money to pay for the first issue. It was money well spent in retrospect. Luckily, the press was very enthused about the magazine - we got very good reviews. At the time it was clear that we were heading for democracy in South Africa, and Bitterkomix was a new and challenging cultural product in a medium that was always considered to be conservative and for children. It certainly got easier as we progressed.

Have the political and social changes in South Africa also been apparent throughout the issues of Bitterkomix and in your own work?

Kannemeyer: This is one of those questions that one can answer well in retrospect - I'm still not sure, though. It's not superficially evident, but there are definitely hints and clues. Although I see myself as a satirist, I do not deal with day-to-day problems in my work (as editorial cartoonists do) - it's a lengthy process in my case, and it takes a lot of time to reflect on issues that inspire me. So the comics magazine did not change as politics changed - we had a position from the outset, and we stuck with it.

Is there a lot of attention for the underground in South Africa? And is the mainstream comparable to the European or American market? (Or maybe I should ask whether Bitterkomix has become South African mainstream?)

Kannemeyer: I think there was more emphasis on the underground as Apartheid came to an end. This underground was present in different media: theatre, music, and literature mostly - as far as comics went, there was really just Bitterkomix and a few newspaper cartoonists. But in retrospect, Bitterkomix came at a very good time, because as the South African market opened up to the world: a lot of curators visited South Africa and Bitterkomix was pretty visible - we got a lot of attention and invitations to exhibit. But you must also remember that we were very offensive (we did some sexually explicit comics, criticising our conservative Calvinist background) and many people were very offended by this. So we were not included in many of the more "proper" exhibitions, we pretty much stayed underground. Today, I wouldn't say Conrad and I are mainstream, but there is a much bigger acceptance of our work. Some people will call this "mainstream" or a "sell-out". Bitterkomix issues have become collector's items and are selling for ridiculous prices on auctions - a lot of this has to do with some big institutions that started collecting our books and work, like the MoMA, the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Kannemeyer: This is one of those questions that one can answer well in retrospect - I'm still not sure, though. It's not superficially evident, but there are definitely hints and clues. Although I see myself as a satirist, I do not deal with day-to-day problems in my work (as editorial cartoonists do) - it's a lengthy process in my case, and it takes a lot of time to reflect on issues that inspire me. So the comics magazine did not change as politics changed - we had a position from the outset, and we stuck with it.

Is there a lot of attention for the underground in South Africa? And is the mainstream comparable to the European or American market? (Or maybe I should ask whether Bitterkomix has become South African mainstream?)

Kannemeyer: I think there was more emphasis on the underground as Apartheid came to an end. This underground was present in different media: theatre, music, and literature mostly - as far as comics went, there was really just Bitterkomix and a few newspaper cartoonists. But in retrospect, Bitterkomix came at a very good time, because as the South African market opened up to the world: a lot of curators visited South Africa and Bitterkomix was pretty visible - we got a lot of attention and invitations to exhibit. But you must also remember that we were very offensive (we did some sexually explicit comics, criticising our conservative Calvinist background) and many people were very offended by this. So we were not included in many of the more "proper" exhibitions, we pretty much stayed underground. Today, I wouldn't say Conrad and I are mainstream, but there is a much bigger acceptance of our work. Some people will call this "mainstream" or a "sell-out". Bitterkomix issues have become collector's items and are selling for ridiculous prices on auctions - a lot of this has to do with some big institutions that started collecting our books and work, like the MoMA, the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Bitterkomix isn’t just about comics. Gregor Straube, curator of "Don't Shoot! We Are Not Armed!" told me the exhibition also tried to include more than just comics. Is it something, you feel, is necessary: the dynamic between art disciplines? Does it enrich what you do?

Kannemeyer: I think there are a couple of answers here. To begin with, we always (from the first issue of Bitterkomix) exhibited our comics in galleries in South Africa. I think the media here (in SA) always saw our comics as a bit different from "normal" comics, because we started off by making large silkscreen prints of some of the works. Another thing is that we never really made any money by selling Bitterkomix. But we did make money by selling art related to Bitterkomix. When I started working with art galleries it opened up opportunities for me to work on larger formats and in different media. Also, truth be told, I'm probably not such a good comics artist in the end - I work slowly and find long narratives difficult to complete. I tend to approach subjects far more conceptually and I'm very interested in an ambiguous message, something that will make the viewer uncomfortable. So I find that I can move between disciplines, but that works for me, maybe not for other artists...

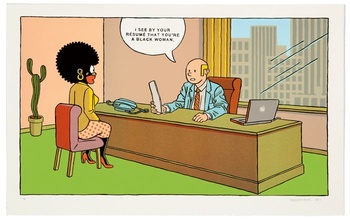

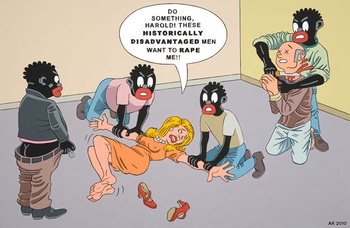

Political correctness is something you shy away from. Did you ever get into trouble because of that?

Kannemeyer: Yes. I've had a lot of trouble for various reasons. I shy away from political correctness because I see it predominantly as dishonest. "Politically correct" reasoning has also become mainstream, and I believe there are different ways of looking at things. It's important to understand though that this does not mean that I'm conservative in my views - in America I find that people tend to polarise these things. They do not see all the shades of grey in between. And the liberals in America still think they're liberal, they do not think of themselves as conservative, which is what they really are. I also got into trouble for using sexually explicit images - somehow people think that's distasteful. I think these people are just being (once again) what they really are: conservative.

Alfred Schaffer, an amazing Dutch poet, who has lived in South Africa for a long time, and is living there again, once stated that, confronted with harsh reality and a brutal world, he couldn’t make honeyed poetry. Is that a thought that might coincide with the foundations of Bitterkomix? Honesty (meaning that the world does find a way into art) above all. And confrontational art to make people think and nuance?

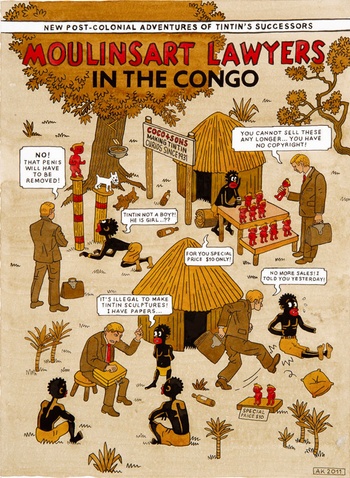

Kannemeyer: Yes, I agree with Alfred. When I first had ideas of being a comics artist one day, my thoughts were about making adventure stories like Tintin. Somehow my circumstances simply did not allow for that. My confrontational work comes from being an Afrikaner. If I were an English-speaking South African, I do not think I would have made the work I did. As an Afrikaner I thoroughly rejected my "people" - I even stopped speaking to my father - and wanted to confront and shock them.

Kannemeyer: I think there are a couple of answers here. To begin with, we always (from the first issue of Bitterkomix) exhibited our comics in galleries in South Africa. I think the media here (in SA) always saw our comics as a bit different from "normal" comics, because we started off by making large silkscreen prints of some of the works. Another thing is that we never really made any money by selling Bitterkomix. But we did make money by selling art related to Bitterkomix. When I started working with art galleries it opened up opportunities for me to work on larger formats and in different media. Also, truth be told, I'm probably not such a good comics artist in the end - I work slowly and find long narratives difficult to complete. I tend to approach subjects far more conceptually and I'm very interested in an ambiguous message, something that will make the viewer uncomfortable. So I find that I can move between disciplines, but that works for me, maybe not for other artists...

Political correctness is something you shy away from. Did you ever get into trouble because of that?

Kannemeyer: Yes. I've had a lot of trouble for various reasons. I shy away from political correctness because I see it predominantly as dishonest. "Politically correct" reasoning has also become mainstream, and I believe there are different ways of looking at things. It's important to understand though that this does not mean that I'm conservative in my views - in America I find that people tend to polarise these things. They do not see all the shades of grey in between. And the liberals in America still think they're liberal, they do not think of themselves as conservative, which is what they really are. I also got into trouble for using sexually explicit images - somehow people think that's distasteful. I think these people are just being (once again) what they really are: conservative.

Alfred Schaffer, an amazing Dutch poet, who has lived in South Africa for a long time, and is living there again, once stated that, confronted with harsh reality and a brutal world, he couldn’t make honeyed poetry. Is that a thought that might coincide with the foundations of Bitterkomix? Honesty (meaning that the world does find a way into art) above all. And confrontational art to make people think and nuance?

Kannemeyer: Yes, I agree with Alfred. When I first had ideas of being a comics artist one day, my thoughts were about making adventure stories like Tintin. Somehow my circumstances simply did not allow for that. My confrontational work comes from being an Afrikaner. If I were an English-speaking South African, I do not think I would have made the work I did. As an Afrikaner I thoroughly rejected my "people" - I even stopped speaking to my father - and wanted to confront and shock them.

Hergé is at least a stylistic reference in your comics, and Tintin in the Congo something you have parodied. Are you an admirer of Hergé, a Hergé critic, or something of both?

Kannemeyer: I think Hergé is the best comics artist of the 20th century. In my opinion he's better than America's big comics artists like Charles Shulz, George Herriman, Robert Crumb, etc. I mean, there are many brilliant comics artists out there that I all admire, but if I'm really honest with myself, I'll take Tintin with me to a deserted island. But Hergé did make Tintin in the Congo, which is really a problematic book. I do not think it's a good book for children, it's a book that grown-ups should read, or teachers should discuss in class with children. It's outright racist, there is no doubt about that. To "forgive" the book as a relic of the time, is too easy for me. But I do not believe in censorship - it should absolutely be available, just maybe not to children. Maybe they should put an age restriction on the book as they do with some music?

You once said that if Bitterkomix would have made a song, it would have been ‘Doos dronk’ by Die Antwoord. We have got to know them and immediately categorised them as cult. Kind of frightening, funny, dirty, and so on. What is it in Die Antwoord that you can relate to?

Kannemeyer: They're politically incorrect and do things from the heart, from instinct. It misses in some instances - I'm not really into this whole hip-hop thing of calling people "faggots" or women "bitches", etc., but I appreciate the energy that comes with it. They're also very set on surprising their audience, not just doing things for the sake of it.

Do you notice shifts in the South African comics scene in time? Some of the young artists in the exhibition haven’t (yet) published in Bitterkomix. Is committed art an obvious thing? (In Belgium, for example, you can see a shift towards worldly issues, comics artists, writers picking up topics that go beyond a personal level.)

Kannemeyer: Firstly, there are not many comics/comics artists in South Africa. I believe comics artists (even South African comics artists) should do whatever they like to do, and with the internet and social media as they are, it's just natural that they would move away from the problems that Bitterkomix dealt with. I read a lot of comics that aren't personal or autobiographical, but the best ones, like good literature, have an element of it. I think a South African comics artist like Joe Daly belongs to a new generation, and I absolutely love his work. So much that he is currently one of my favourite comics artists. But the best comic I have read last year, Jerusalem by Guy Delisle, was pretty much socio-political autobiography.

READ OUR INTERVIEW WITH GREGOR STRAUBE, CURATOR OF DON'T SHOOT!

Kannemeyer: I think Hergé is the best comics artist of the 20th century. In my opinion he's better than America's big comics artists like Charles Shulz, George Herriman, Robert Crumb, etc. I mean, there are many brilliant comics artists out there that I all admire, but if I'm really honest with myself, I'll take Tintin with me to a deserted island. But Hergé did make Tintin in the Congo, which is really a problematic book. I do not think it's a good book for children, it's a book that grown-ups should read, or teachers should discuss in class with children. It's outright racist, there is no doubt about that. To "forgive" the book as a relic of the time, is too easy for me. But I do not believe in censorship - it should absolutely be available, just maybe not to children. Maybe they should put an age restriction on the book as they do with some music?

You once said that if Bitterkomix would have made a song, it would have been ‘Doos dronk’ by Die Antwoord. We have got to know them and immediately categorised them as cult. Kind of frightening, funny, dirty, and so on. What is it in Die Antwoord that you can relate to?

Kannemeyer: They're politically incorrect and do things from the heart, from instinct. It misses in some instances - I'm not really into this whole hip-hop thing of calling people "faggots" or women "bitches", etc., but I appreciate the energy that comes with it. They're also very set on surprising their audience, not just doing things for the sake of it.

Do you notice shifts in the South African comics scene in time? Some of the young artists in the exhibition haven’t (yet) published in Bitterkomix. Is committed art an obvious thing? (In Belgium, for example, you can see a shift towards worldly issues, comics artists, writers picking up topics that go beyond a personal level.)

Kannemeyer: Firstly, there are not many comics/comics artists in South Africa. I believe comics artists (even South African comics artists) should do whatever they like to do, and with the internet and social media as they are, it's just natural that they would move away from the problems that Bitterkomix dealt with. I read a lot of comics that aren't personal or autobiographical, but the best ones, like good literature, have an element of it. I think a South African comics artist like Joe Daly belongs to a new generation, and I absolutely love his work. So much that he is currently one of my favourite comics artists. But the best comic I have read last year, Jerusalem by Guy Delisle, was pretty much socio-political autobiography.

READ OUR INTERVIEW WITH GREGOR STRAUBE, CURATOR OF DON'T SHOOT!

Read more about: Expo

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.