In Beijing, between 2009 and 2013, the French collector and curator Thomas Sauvin rescued more than half a million colour negatives from destruction. The exhibition "Beijing Silvermine" puts this fascinating collection of contemporary Chinese snapshots on display.

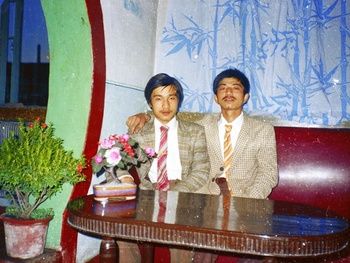

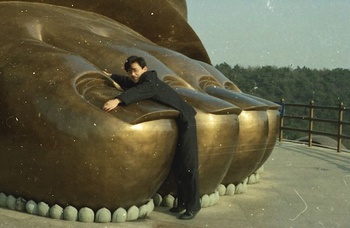

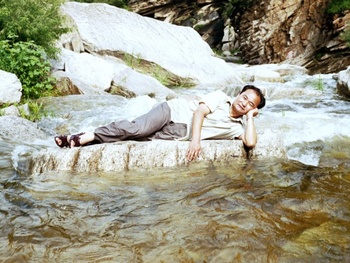

"Beijing Silvermine" is an archive, as fascinating as it is varied, that spans twenty years and is chock-full of snapshots of Chinese people posing alongside their fridges, tourist attractions, and Ronald McDonald. The French collector and curator Thomas Sauvin bought them, by the kilo, from one Xiao Ma, who in turn had collected them with a view to filtering out their silver nitrate. Sauvin’s connection with Beijing, however, had its roots, not in images, but in the written word.

Beijing Silvermine: China in snapshots

“I was struggling with dyslexia and started to learn Chinese at the age of thirteen – drawing those characters helped,” says Sauvin. “At seventeen, an exchange programme offered me the opportunity to go to China. I thought it was great to be away from home and to be able to smoke in the street, in taxis, and in hospitals. After completing a depressing management course, I went to work as an assistant to the French curator Alain Jullien during the Lianzhou International Photo Festival. At the end of the festival I met a collector from London, who asked me to buy a few prints for him. So I started to collect Chinese contemporary photography. I did that for three years, until, in 2009, I started to look more at everyday things: scholarly reports, posters, and postcards. At first, I mainly went around junk markets, looking for photo albums. What surprised me then was that buyers concentrated on a limited period and a limited number of subjects: Mao, the Red Guards, Tiananmen Square, and the Cultural Revolution. Undoubtedly very important in Chinese history, but very restricted in terms of subject matter. Those prints, moreover, were always too expensive; so I asked them if they had any other stuff. Yes, they said, but it’s rubbish. But when I took a look at it, I always found it more interesting, precisely because it was about the periods that were always ignored.”

Why did you drop the photo albums and decide to concentrate on negatives?

Thomas Sauvin: Because, with the negatives, I get the whole roll of film. In a photo album, you only get to see the pictures the photographer chose, for whatever reason. I’m not interested in their personal selection: that has no significance for me. By getting my hands on all the negatives, I have a more complete picture.

There is something quite bizarre, somehow, about people just throwing away their negatives.

Sauvin: A professional photographer would never do that, but we’re talking here about amateurs only. I don’t have a ready-made answer, but I think the negative, over time, just becomes a meaningless object. Someone who has taken photographs of his children over many years prints some favourite pictures to stick in an album and that’s that. The photograph album is important; the negatives aren’t. A time comes when they are thrown away, by the photographer himself or, after his death, by the children, who aren’t willing to put any energy into them. The family album is still there, after all.

Thomas Sauvin: Because, with the negatives, I get the whole roll of film. In a photo album, you only get to see the pictures the photographer chose, for whatever reason. I’m not interested in their personal selection: that has no significance for me. By getting my hands on all the negatives, I have a more complete picture.

There is something quite bizarre, somehow, about people just throwing away their negatives.

Sauvin: A professional photographer would never do that, but we’re talking here about amateurs only. I don’t have a ready-made answer, but I think the negative, over time, just becomes a meaningless object. Someone who has taken photographs of his children over many years prints some favourite pictures to stick in an album and that’s that. The photograph album is important; the negatives aren’t. A time comes when they are thrown away, by the photographer himself or, after his death, by the children, who aren’t willing to put any energy into them. The family album is still there, after all.

You mainly work on themes, codes, and patterns that emerge. You’re not interested in individual stories.

Sauvin: My collection contains about 650,000 pictures. To reduce that to something that feels like the sum of a few anecdotes, in which you see someone grow up, get married, and get divorced, doesn’t really seem meaningful to me. I did see stories like that in the negatives: a man who worked in a factory with yoghurt packaging and was sent to Africa as a consultant by his company. He travelled there for eight years, which resulted in a fine series of portraits with Africans on the one hand and yoghurt packaging on the other. Highly amusing and fun for me to disentangle, but not really representative of an era. I never deliberately set out to work with those themes. It grew organically, after spending a few years with those negatives. What finally came to the surface, I could never have dreamt up myself. A series of photographs of women posing by their fridges, you couldn’t make that up. But when you put them into historical perspective, it makes complete sense. Those pictures were only taken over five years, during the period when Chinese households were modernising.

The archive is gigantic and has great value for scholars. Whereas lots of people would treat it very seriously, you keep things noticeably light-hearted.

Sauvin: Above all, I wanted to show a different picture of China. It’s not propaganda and it’s not criticism either. I have been living in China for twelve years now and I have a problem with how other photographers or journalists again and again approach the country from the same angles: human rights, Ai Weiwei, Tibet, the Dalai Lama, pollution... Those are important subjects, but there is more to China. People often say to me that they had never seen the country in that way. They didn’t expect to see any love or any humour.

Sauvin: My collection contains about 650,000 pictures. To reduce that to something that feels like the sum of a few anecdotes, in which you see someone grow up, get married, and get divorced, doesn’t really seem meaningful to me. I did see stories like that in the negatives: a man who worked in a factory with yoghurt packaging and was sent to Africa as a consultant by his company. He travelled there for eight years, which resulted in a fine series of portraits with Africans on the one hand and yoghurt packaging on the other. Highly amusing and fun for me to disentangle, but not really representative of an era. I never deliberately set out to work with those themes. It grew organically, after spending a few years with those negatives. What finally came to the surface, I could never have dreamt up myself. A series of photographs of women posing by their fridges, you couldn’t make that up. But when you put them into historical perspective, it makes complete sense. Those pictures were only taken over five years, during the period when Chinese households were modernising.

The archive is gigantic and has great value for scholars. Whereas lots of people would treat it very seriously, you keep things noticeably light-hearted.

Sauvin: Above all, I wanted to show a different picture of China. It’s not propaganda and it’s not criticism either. I have been living in China for twelve years now and I have a problem with how other photographers or journalists again and again approach the country from the same angles: human rights, Ai Weiwei, Tibet, the Dalai Lama, pollution... Those are important subjects, but there is more to China. People often say to me that they had never seen the country in that way. They didn’t expect to see any love or any humour.

You work with other artists, such as Melinda Gibson and Lei Lei. How important is that collaboration for you?

Sauvin: Very important. I have my own approach, which is primarily anthropological. Their ideas force me to look at the archive in a different way and to set about digging up new things. They change the game. For example, I often cooperate with a town planner in Beijing who focuses mostly on mobility and how developments in that sphere had an impact on people’s lives.

Is it your goal to also show us that the Chinese are not that different from us Westerners?

Sauvin: It is always kind of tricky to make out that Chinese people are not so different from us – the fact is they are. But when it comes to everyday photography, then there are indeed a lot of similarities: children, travel, free time, family parties... Those are the same triggers to press that little button. At exhibitions in the West, I often hear people say they found certain pictures familiar, because they had taken them themselves at some point. But at an exhibition in Hong Kong, on the other hand, the public reaction was more of boredom, precisely because they saw pictures that, after all, they had at home themselves.

BEIJING SILVERMINE + wang bing • 20/9 > 1/11, di/ma/tu > za/sa/Sa 11 > 19.00, Galerie Paris-Beijing, Hôtel Winssinger, Munthofstraat 66 rue de l’Hôtel des Monnaies, Sint-Gillis/Saint-Gilles, 02-851.04.13, www.galerieparisbeijing.com

Sauvin: Very important. I have my own approach, which is primarily anthropological. Their ideas force me to look at the archive in a different way and to set about digging up new things. They change the game. For example, I often cooperate with a town planner in Beijing who focuses mostly on mobility and how developments in that sphere had an impact on people’s lives.

Is it your goal to also show us that the Chinese are not that different from us Westerners?

Sauvin: It is always kind of tricky to make out that Chinese people are not so different from us – the fact is they are. But when it comes to everyday photography, then there are indeed a lot of similarities: children, travel, free time, family parties... Those are the same triggers to press that little button. At exhibitions in the West, I often hear people say they found certain pictures familiar, because they had taken them themselves at some point. But at an exhibition in Hong Kong, on the other hand, the public reaction was more of boredom, precisely because they saw pictures that, after all, they had at home themselves.

BEIJING SILVERMINE + wang bing • 20/9 > 1/11, di/ma/tu > za/sa/Sa 11 > 19.00, Galerie Paris-Beijing, Hôtel Winssinger, Munthofstraat 66 rue de l’Hôtel des Monnaies, Sint-Gillis/Saint-Gilles, 02-851.04.13, www.galerieparisbeijing.com

Read more about: Expo

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.