Hands up! South African underground comics

A hellish roar is coming from the bowels of the Station Brussel-Kapellekerk/Gare Bruxelles-Chapelle, where Recyclart is opening its doors to South African underground comics with the exhibition “Don’t Shoot! We Are Not Armed!” On the opening night, all hands are in the air for DJ Nie Bang Nie, Frisk Frugt, and Awesome Tapes From Africa.

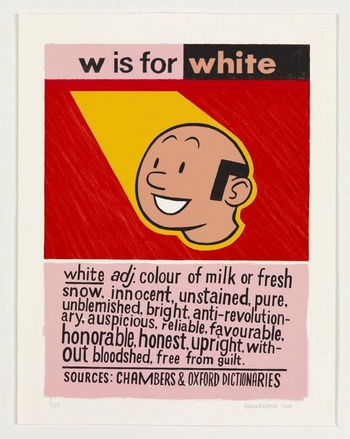

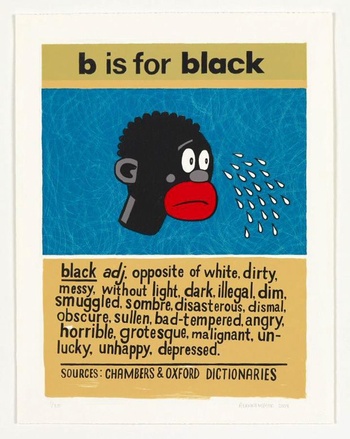

A perverse, terrifying thought goes through our mind. What if you scream “Don’t shoot! We are not armed!”, but there are no hands to stick up? Whoever thinks the arts aren’t dangerous should watch the reaction of the Hergé Foundation when they see the work of the South African comic book artist and founder of the razor-sharp comic strip magazine Bitterkomix Anton Kannemeyer, who is featured in the South African underground comics exhibition at Recyclart. “What Anton does in his comics, is use aesthetics and racial stereotypes to address the racist fears in the minds of the white, liberal middle-class in Africa. Holding a mirror up in front of the people that abolished the Apartheid system, but that still have those old patterns of thought lingering in their subconscious,” says Gregor Straube, the exhibition curator. The German comics lover speaks passionately and with nuance about the South African comic strip scene, which he discovered almost by accident. “Yeah, you could call it a mere accident. [Laughs] Danie Marais, one of the artists in the exhibition, used to live in Bremen. He is a poet, but he knows all the guys from Bitterkomix. Through him I got to know a little bit about South African comics, and the varied Cape Town scene in particular. And then one thing led to another.”

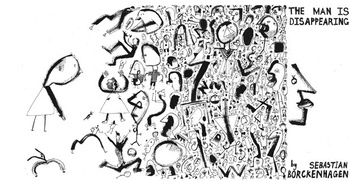

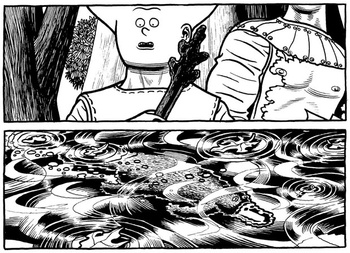

The presence of Danie Marais is a clear indication of the exhibition’s breadth. “Actually, I’m only partly exhibiting comics: there are some original drawings, a complete story, some frames, but there is also more graphic art by Sebastian Borckenhagen, Joe Daly, or Mark Kannemeyer, referring to the style and aesthetics they use in comics, or to the comics tradition. And you have some collaborations with poets, like comic strip artists Nathan and Andre Trantraal who have been collaborating with Ronelda Kamfer, a young and very interesting coloured poet. Danie made the texts for a comic by Karlien de Villiers. And there are also two animated short films by Diek Grobler, which accompany poems by Danie. So it’s a combination of language and visual art, rather than comics in a strict, conservative sense.”

This multidisciplinarity and openness is also what attracts Gregor Straube to comics: “I’m not a comic artist myself, I was always more of a consumer. But comics have been part of my life since I was a kid, when my father bought me my first Asterix. What I like most about them is this combination of the written word and the visual aspect – though some comics don’t even need words. But there is always a story being told. It’s that combination of things that are not necessarily considered to belong together – like paintings and literature – that I like about comics, and it is something I integrated in the exhibition as well.”

Enter the narrative aspect, which in the best case creates a third dimension from the combination of text and images. Storytelling is an act of remembrance in some cases. The Trantraal brothers and Anton Kannemeyer seem to look at comics as a means of making things discussable, making latent or unspeakable issues public property. “Yes, that’s especially true for the Trantraals. They became famous for a comic that was called Coloureds. In South Africa they distinguish between black, coloured, and white people. It’s kind of a heritage of the Apartheid system, ‘coloured’ being a derogatory term, strongly connected to that system. The Trantraal brothers have been using these kinds of distinction, belonging to the coloured community themselves. Calling your comic Coloureds, especially one that is widely discussed in the media, makes people use a word which they feel uncomfortable using. In that comic series, made in a Japanese manga style, the Trantraal brothers tell stories about childhood, about growing up in the township, in poverty, and about all the things that are related to that situation, ranging from religious ideologies to violence and abuse. They write stories about people whose stories aren’t being told.”

And it is very clear that there are stories that aren’t being told in a country that did not abolish institutionalised racial segregation until the 1990s. “South Africa is a harsh society. Racism and the consequences of the Apartheid system, remain skin-deep under the surface. It is not eradicated at all. I recently visited the country for two months, and there’s always this tense atmosphere – or at least that’s what I experienced. There is so much history that has not been dealt with yet. And no recompense has been properly made by the exploitative side during the Apartheid system. The vast majority of non-white people still live in extreme poverty. It is really hard to describe. People don’t have faith in politics to bring change anymore. The ruling parties are doing exactly the same thing parties during the Apartheid had been doing: reaping profits on the back of the impoverished classes. There isn’t much faith, but there is a lot of repressed anger and violence, as well as a lot of repressed racist stereotypes.”

That was and still is the ideal breeding ground for a magazine like Bitterkomix, created in the hallways of the fine arts department of the university of Stellenbosch in 1992. Anton Kannemeyer and Conrad Botes created a visually versatile and experimental annual magazine, with razor-sharp, provocative, and anarchic content, which is just as dirty as the dirtiest rhymes from Die Antwoord. Anton Kannemeyer once said that if Bitterkomix were to go into music, it would produce a song like “Doos Dronk”. Conversely, Anton Kannemeyer – as a source of inspiration – had a part in the acerbic music video of “Fatty Boom Boom”, that caused a very public conflict with Lady Gaga. “I think what Bitterkomix did was address issues that people in South Africa did not want to talk about. Those issues are sexuality and sexism, race and racism, quite often also religion, and they are addressed in a very drastic way. Especially Mark, Anton, and Conrad address these issues quite often. The generation of the founders of Bitterkomix, who have in turn ended up teaching other artists, has had a big influence on the underground comics scene, including aesthetically.”

Young artists like Sebastian Borckenhagen never published in Bitterkomix. His style is highly particular, and though he is politically aware, he does not use his art as a means of political expression. The same goes for Joe Daly, a major league player with a spot on US editor Fantagraphics’s team, who does not have political inclinations. Finally, humour is also a nuanced genre: “Not all the artists use humour. The Trantraals use humour as a means of transporting their views and ideas. In Bitterkomix, the humour is jet black. You laugh at it because you just don’t have any other option. Often they ridicule the whole liberal politically correct approach. Just because we don’t use certain language anymore, doesn’t mean we got rid of the racist structures underlying society and interaction. But how else can you deal with this situation? It’s laughing so as not to cry.”

Don’t Shoot! We Are Not Armed! 5 > 11/4, 12 > 17.00 (opening: 4/4, 20.30 > 1.00), Recyclart, Ursulinenstraat 25 rue des Ursulines, Brussel/Bruxelles, 02-502.57.34, info@recyclart.be, www.recyclart.be

READ OUR INTERVIEW WITH ANTON KANNEMEYER

Read more about: Expo

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.