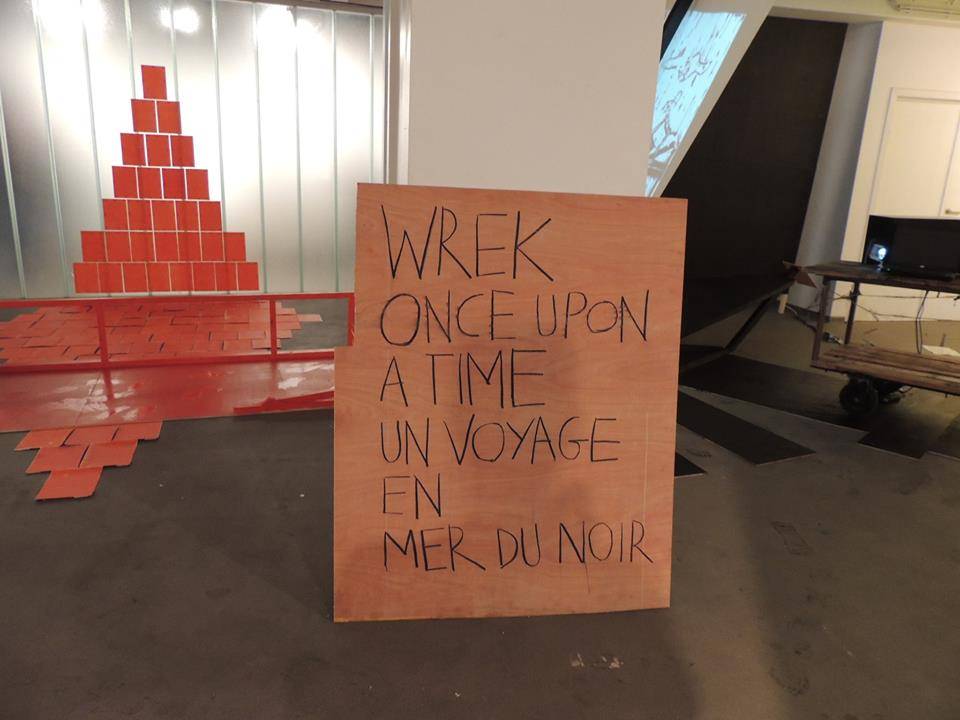

After “The Naughty Girl & The Naughty Boy” and “Fucking Hell”, the extraordinary revolutionary unit consisting of Miles O Shea, Olivier Deprez, and Marine Penhouët is back with “WREK Once Upon A Time Un Voyage En Mer Du Noir”. This time, at Cultures Maison, the festival with a giant heart for what comics are and can be, where WREK is, as always, stretching boundaries and challenging existing categories. Gone are the dark days, red is the new black!

Red is the new black: WREK at Cultures Maison

An interview with WREK – a play on the German word Werk, or rather a new alphabet for a countercultural approach – is always an agreable conversation, circling around topics that become poignant just before they take up their place in the margins of things and thoughts again. It’s a series of incisive words only carving out a silhouette. A construction built on the spot, on a foundation of years of experience and reflection, yet prepared to change, evolve, develop into something that has never been expressed before. It is time spent in negative space, around and between a subject that becomes more relevant with every word that is said. Like the blank space on a page where readers are free to roam between the words. With the unique characteristic of that blank space – here some sort of art noir – eventually taking over the whole image, or the other way around, with the image blurring into negative space.

If you have noticed that we aren’t sure of a thing we are saying, it is because where WREK lives and exists, a firm dose of negative capability, as John Keats describes the capacity of being in uncertainties, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason, is a welcome one here. “I think WREK will be over when it enters the age of reason,” says Miles O Shea, together with Olivier Deprez and Marine Penhouët part of the three-headed oneness that is WREK. “What is it about? That is a question that is impossible to answer. The information is not yet available.”

But let’s give it a go. WREK is reclaiming comics, making animation films from woodcut prints, walking around with a “RollerTableTower”, filming a mountain’s flat surface or an arm that caught fire, printing black pages, and repeating that process over and over again. That is what it does. What it incites, is something completely different: they sever moments from time, stretch them out with amazement, insert doubt, create unrest, comfort you, draw you out of prevailing paradigms for a total renaissance, tell you things were never any different, foster the paradox, and then bring you back to the essentials. Nothing more, nothing less. Or to put it in the words of Miles O Shea, when we interviewed him a few months ago: “It’s about working, about making, about the process of work, and how that fits into your life. Even life is just the end product of your work. But that isn’t our focus. That is the process, what you do.”

CALL IT WHAT YOU WILL

There is no need for a clear-cut answer, because it isn’t the destination that matters, it is the road and where you are now. As is the case at Cultures Maison, where WREK has installed a boat, is projecting a film made from woodcuts on the sail, and evoking a sea of red prints… Red?!? “The reason? Well, the time just felt right,” laughs Miles O Shea. “‘WREK Once Upon A Time Un Voyage En Mer Du Noir” is a very just put together title, like “WREK Manifesto Natives Of Abstraction”, our exhibition at Le Vecteur in Charleroi earlier this year. It can be read as a phrase and yet you have these sharp edges. The title almost is the directive of WREK to the viewer to say this is what you have to work with.” Olivier Deprez: “To me, the title is almost like a novel. It is very mythological, very collective, you have all these stories popping up in your mind, that create so many doors for you to enter. The mer du noir is a red one, it creates an illusion, and a very powerful one. What you read is not what you see. And that creates a tension that is linked with the idea of narration and the idea of visualising comics. Is this boat the model for a bigger one? Or is it the real boat? Is it about to go on a journey or has it just come back? It’s many things. And considering all of those, suddenly the room changes. It is full of electricity, narration. This tension is extraordinary, full of poetry, full of images…”

STORMING THE CITADEL

It’s a radical practice, a radical view, and there is a radical thought behind it. Thought, not reason. “A very rough shift of meaning,” Miles O Shea calls it, “always becoming and never getting there, always releasing meaning. Right from the beginning, nine years ago, when we made these black books for libraries, it was to put them into the catalogues of libraries. The book goes into the institution, it’s an intervention. It does have something of storming the citadel, the status quo, the nice careful easy ‘let’s make some things, this is what art is, now you can all go back to sleep’. If anything, it’s an attack on what I perceive as boring contemporary art.”

Olivier Deprez: “WREK has a way of being in the world that tries to be on the other side of reason, that thing that determines everything. WREK is in a position where it dissolves categories and borders between things. At Cultures Maison, we are some form of questioning of comics. Is comics a category in itself? Are you making comics from the moment you divide the page into squares? From the moment you are a comics writer, does that mean you’re making comics? WREK puts a lot into question. We are in the margins of all of that, or rather in the centre, making the whole thing explode. Even for us there is a side to WREK that we can’t grasp. I have always had trouble calling myself a comics artist, but I have never questioned my being part of WREK. It’s the place where categories are dissolved.”

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE FOURTH KIND

“WREK is some sort of invention,” says Miles O Shea. “We have invented this artist called WREK, which allows us – and this is what I like about it very much – to get away with stuff that you normally wouldn’t be able to get away with. ‘It’s not me, it’s WREK doing this.’ I have always wanted to be Jean-Pierre Léaud from Godard’s La Chinoise, and that is now possible. WREK allows the taking on of a role. That is why I insist on WREK not being a three-person collective. It’s one thing, a shared experience.” Olivier Deprez: “In a way, we leave the ego in the waiting room. We experiment, and that makes it hard to define what it is we do, or who it is that does what we do. Ultimately WREK blurs the boundaries and categories of the ego, the moi.” Miles O Shea: “I would hope WREK is very selfless, in the sense that is very welcoming. There is space here for you. In this day and age of rampant consumerism and capitalism, this whole idea of the moi and satisfying the ego is a bloody waste of time. WREK will never be a tour de force, a maestro, or about mastering a technique… It will never be: ‘Yes, and now we’ll have some applause.’ That’s just cruel, stupid vanity.’ WREK’s trajectory, ambition, drive, or direction is not vertical. It’s not going up, getting up, it’s horizontal, spreading.”

Olivier Deprez: “Exactly. Throughout the years WREK has taken on a life of its own, really. Quite independently. We feel WREK escapes us completely. It exists, people talk about it, but we don’t own it anymore. The three of us enter into this space where we can do ‘WREK things’. It’s like a playground.” Miles O Shea: “It validates itself, yes. If you look at popular music, art, or literature: it’s the formula which repeats itself over and over again, and ultimately it doesn’t have anything. WREK is like the shadow side of that, it is an intervention, like in Modern Times Charlie Chaplin breaking the machine, putting the spanner in the works. I think that’s much much more interesting. It brings things into the world. It’s not anti-art, anti-populism… I think what WREK does is it fills a gap or exposes that gap. If the art you see at Bozar or the Venice Biennale is the art of the first world, and the third world is Arte Povera, then you could say WREK is from the fourth world. With the fanzine being the holiday brochure.” Marine Penhouët: “Welcome to WREK World!” [Laughter]

Read more about: Expo

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.