In a time where the urban and digital grid alienate us from our own bodies, the work of the British Turner Prize-winning artist Antony Gormley reconnects us to our essence and potential. His sculptural bodies, doorways to the space behind our eyes, are now on view at Xavier Hufkens.

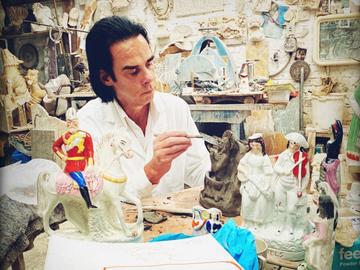

© HV-Studio

Also read: Brussels kunstenaar Walter Swennen overleden

Close your eyes. Now, where are you? What can you feel? What can you see?” On the screen that connects us, Antony Gormley (72) turns in on himself, eyes wide shut, and allows his thoughtful, spontaneous but carefully formulated words to expand into a space vibrating with potency. “This…is a space without edge, without dimension, without objects…that is infinitely extensive.”

For a brief moment, I doubt whether to join him in his journey, but the curiosity to witness this unique moment prevails over the darkness that is lurking within. The background on the screen, a corner of Antony Gormley's bright London studio, fades away, as the renowned and cherished British sculptor treads ever deeper into “this subjective but collective place.”

“I still think it's an absolute mystery, a paradox and a miracle that in the core of each of us is this direct experience of the infinite, the unknowable, the ineffable that lies behind and beyond everything that we think of as 'world' or even as 'life',” he says upon leaving the space behind his eyes. A space that he at first felt convicted to when being sent upstairs as a child for half an hour of “enforced immobility and rest” after lunch, but that he eventually learned to love to venture into. To this day, after decades of sculpting, that space remains the place that pulls at him, that he returns to and that he wants to evoke and stir inside of us. When all is colonised, the journey inwards allows for freedom.

These bodies are shadows, traces that mould in time a moment of human life, of living, of living time. They are waiting. They are waiting for the time of the viewer to inhabit and enliven them

“So we have this potential of a direct apprehension of a space that lies outside time and objects, but having made this realization – which on some level is so commonplace and yet we all spend our lives turning away from this reality of inner darkness – what do we do with it?” Well, Antony Gormley sculpts. He creates traces, “forensic evidence of where a singular individual body once was, where any body, by implication, could be.” Whether it is an empty box in human form, “to say: 'Here is a human space'”, whether it is the bodies moulded and cast and imagined from his own body, either physically or digitally, or bodies that evoke the built environment, “our second body” as Antony Gormley calls it. It is taking minimalism and conceptualism, accepting the material condition of being, but adding to it, by “bringing back the notion of the body as a vehicle for the infinite to the language of sculpture, that has become very much about either process or material form. It is telling us that even in an industrial, constructed, made environment, we find a body that carries feeling as well as thought.”

© HV-Studio

“So these bodies are not representations, they are evocations, they are instruments of self-knowing. And the body in question is no longer my body, it is the body of the viewer and their ability to imaginatively or physically enter the spaces that the works construct or evoke. (Pauses) It's a very tall order, I understand that. We are living in a visual time, we expect narrative and representation, and these things resist that expectation. They are not symbolic, they're not even emblematic. They are shadows, traces that mould in time a moment of human life, of living, of living time. They are waiting. They are waiting for the time of the viewer to inhabit and enliven them.”

GIANT

Antony Gormley's work unlocks an empathic space, a space that deep within the self establishes a foundation for the collective and which therefore touches us, sometimes deep into the soul. From his Bed, which visualises an absent body as an empty, self-digested space in a bed of bread, to his Angel of the North, a twenty-metre-high sculpture in Gateshead that has become one of Britain's most beloved landmarks, to his collective Field works. From Passage, a physical evocation of the darkness within, and his bodies concealed in inner postures, to the deeply stirring Sleeping Place that he made in 1973 having come back from his journey to India where he studied Buddhism: “It was just a hospital sheet dipped in plaster and placed over a friend. As a memory of people in India sleeping on the streets and on station platforms. Those were powerful indicators of how you could abstract a place of great intimacy in space at large. Spaces of stillness and interiority with all the world moving around it.” Spaces of stillness that echo deafeningly today in the cardboard tents of young asylum seekers that were recently destroyed by Brussels police.

When I decided not to become a Buddhist monk but to become a sculptor instead, the choice was very clear to me. Either I was going to spend my time in stillness and silence, or I was going to make things that expressed in their stillness and silence some idea about our potential for transformation. I chose the latter

Antony Gormley's work stands tall in the world, confrontational and diagnostic. Ever changing. “We live first in a body, the physical, biological body, that is then insulated by clothes, rooms, houses, buildings, villages, towns, cities and so on. Increasingly, this condition of our urban dependency has become the language of the work. So I have transferred from as it were these very intimate boxes to now making bodies, either solid or void, that are made of boxes. But I want the boxes, these objects that are both thing and place, to be unheimlich, uncanny enough to challenge you, but heimlich or gemütlich enough for you to think: 'Ah, I know what that feels like', and to feel welcome to dwell in it and with it.”

© Lars Gundersen

The use of German is not a coincidence. “My German side is getting stronger and stronger,” the son of a father of Irish descent and a German mother says laughingly when I point out to him how solemnly he speaks about his work. That German lineage recently enabled Antony Gormley to apply for a German passport, from discontent with the Brexit. He is even planning to create seven “Brexit giants” off the coast of Brittany. “I am sad and embarrassed about Brexit and the sense that we have betrayed the ongoing project which is Europe,” he says. “Brexit is a disaster in many ways and plays into identity politics and the rising sense that nationalism and dictatorship have overcome all of the promises of globalisation. Germany has shown itself as a bridging ground in a time of mass migration in its generosity to successive waves of human beings fleeing war, persecution and climate change. It is an inspiration to us all. In the failure of the moral hold of organised religion and the disintegration of party politics, art remains an open ground in which the big questions about human future and purpose can be materialised and shared and can catalyse the necessary transformations.”

RESONATING CHAMBER

These are great expectations, but Antony Gormley is dead serious. “I'm not very comfortable with the fact that I'm so serious about everything, but I think there are a lot of things to be serious about. We live in a time of distraction, where art itself has become a source of distraction and spectacle. Making instruments of self-reflection and reflexivity is what I think art can do, and sculpture in particular.”

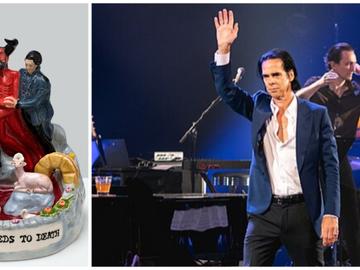

© Photograph by Stephen White & Co © the artist

| Antony Gormley: RETREAT (FRAME), 2021 - cast iron 80 x 49 x 68.6 cm

What was the promise that sculpture held? “I always made things, from very young. All kinds of things, alchemical mixtures and smells and poems… And when I spent three years travelling in India, I did a lot of drawing. And I just didn't trust these registrations of the world. They were useful as a visual diary, but sculpture went beyond that. It offered the opportunity of changing the world rather than representing it or referring to it, because it was displacing materials, transforming them and then putting them back into the world. Here is an object in the world that is not quite of it and that demands us to find a relationship with it. Everything that we have, sculpture lacks. We have movement, we have freedom of expression, and this object then becomes a resonating chamber in which we become more aware, through its stillness and obdurate physicality, of our jeopardy and ability.”

I am sad and embarrassed about Brexit and the sense that we have betrayed the ongoing project which is Europe. Brexit is a disaster in many ways and plays into identity politics and the rising sense that nationalism and dictatorship have overcome all of the promises of globalisation

“My model for that is the most ancient art that we know, which is the standing stone. Our ancestors saw this naturally formed stone that might have lain in a river bed or might be cracked and exposed through the action of the elements, and thought that it was worth standing this stone up, thus creating a marking in space and a measure of lived time. And that remains for me what sculpture can do. It doesn't need all of the frames, even these words are in a way a limitation of what it can do, which is to allow the moving, thinking, feeling, being of things that exist within the biological realm to be tested against the geological time, deep time, planetary, telluric time. When I decided not to become a Buddhist monk but to become a sculptor instead, the choice was very clear to me. Either I was going to spend my time in stillness and silence, or I was going to make things that expressed in their stillness and silence some idea about our potential for transformation. I chose the latter.”

INWARD EXPANSION

All art starts in the personal, the space that embodies the self. That intimacy is a condition, not an end. Antony Gormley's body is his raw material. It is a particular body, which some today see as too restrictive, throwing in the caveat that he is spreading his own image around the world. “To be an artist, there has to be a degree of narcissism, you take your own experience maybe more seriously than others. Every artist wants the particularity of their own experience to be universal and to be of some help to others. I am aware that I may be completely unrealistic in that, that actually these things have little real purchase on the reality of people's lives. But the idea that I'm surrogately erecting these statues to myself, is a singular misreading of what my ambition is. I want to collapse the artist model, the sovereign self that looks out to an objectified world. I want to recognize that the other is oneself and one remains a stranger to oneself. Our self emerges through relations with other bodies and with space, time and everything contained in them. These bodies are registers of a lived moment of human time that is of necessity subjective, intimate and particular, and I'm not making excuses for that. So yes, this is a particular body but it is a case that argues for a collective embodiment.”

© HV-Studio

“It is a way of confronting myself with myself, and myself as a stranger to myself, and inviting myself and others to interpret this, the same way a mirror does, though hopefully in a more persistent way. The power of sculpture in its resistance to life is also the power of it asking these questions that have nothing to do with memorial and the past but everything with the future: What is man? What is sculpture? What can they become? And what is necessary for them to realise their nature in nature? So this isn't statue making, memorialising or idealising a past or a person. These are means against which we sense our own being. And at this time, where we are so distracted, where we are living a gridded experience and our bodies have become redundant in a way, because of this whole range of technologies that support the body and actually limit its acute ability to be in context, the need for these models is greater than ever.”

So at Xavier Hufkens, you will come across RUN III, a three-dimensional drawing that registers and delineates the context of the human animal, but where walls become doors and windows become walls…and that hopefully “begins to influence the choreography of your own movement through time and space.” Corner, “where I'm objectifying the fact that we are in the second body completely,” is a bunker, based on the minimum space a human body needs.

These bodies are registers of a lived moment of human time that is of necessity subjective, intimate and particular, and I'm not making excuses for that. So yes, this is a particular body but it is a case that argues for a collective embodiment

We have come full circle. “Within the limits of a single body lies infinity,” Antony Gormley says. “The commodification of collective space and it having been invaded by all of the forces of municipal management and late capitalist display, the creation of false desires and unnecessary needs, means that the zone of the expansion of human experience has to be inwards, not outwards. That space of embodied consciousness which is the darkness of the body remains the constantly available space of freedom. I think of it as a source of all potential and imagination. So where we started in our conversation, that's where I would conclude it: with a space that is available to us all in the particulars of our individual lives but is also an open space of becoming available to all.”

ANTONY GORMLEY: BODY FIELD

> 17/12, Xavier Hufkens, www.xavierhufkens.com

Read more about: Expo , Antony Gormley , Body Field , Xavier Hufkens