Marina Pinsky was born in Moscow, grew up in the US, exhibited at Wiels and New York's MoMA, and now divides her time between Brussels and Berlin. Both cities feature in her fourth solo show “Four Color Theorem” at C L E A R I N G. As do Google Maps ancestor Theodor Scheimpflug, a mysterious golden hat, a bronze puzzle of Koekelberg, and a gorgeous game of hopscotch between map and territory.

© Ivan Put

| Marina Pinsky at work: “Now that my long hibernation is over, I’m pulling the craziest, longest days.”

WHO IS MARINA PINSKY?

• Born in Moscow in 1986

• Moved to the US when she was three

• Studied fine arts in Boston and LA

• Worked in a professional dark room, printing for other photographers, in New York

• Is currently dividing her time between Brussels and Berlin

• Has had solo shows in Milan, Brussels, New York, Basel, Sydney, Berlin, and Los Angeles, and has been featured at Wiels, the MoMA in New York, and S.M.A.K.

• Is part of the collections of the MoMA and the Flemish Community

“The lockdown happened the week we were supposed to start installing the show. Since all of the works had already been brought here, my studio was completely empty, and I didn't really feel like starting any new artworks. So I ended up on a yoga journey, doing some gardening, and growing my own courgettes. Crazy, right?” Marina Pinsky says laughingly, while taking a break from setting up “Four Color Theorem”, her fourth solo show at C L E A R I N G. “I had been working on these pieces for a year already, so somehow a few weeks delay didn't seem like a huge deal. But you do go through this ritual, where you have this huge climb followed by a big celebration. Breaking that ritual was harder than I thought.”

“One month into the quarantine, I started coming here on my own. I hadn't left my house at all, so it was a colossal effort to get on my bike and get here. But when I did it was incredible! I had this dopamine rush from just being in a different place and seeing other people. (Laughs) And then I started coming every day. Now that my long hibernation is over, I'm pulling the craziest, longest days.”

Putting up a show is a ritual you go through, a huge climb followed by a big celebration. Breaking that ritual was harder than I thought

“Four Color Theorem”, the first exhibition that the Brussels branch of the prestigious New York-based gallery is presenting after being closed for almost three months, has generated a palpable energy in the enormous gallery space in Vorst/Forest. Painter's tape delimits two murals of a building and a truck, a few dozen bronze city models are spread out over the floor, and from the vaulted ceiling hang steel cables that will soon suspend seven imposing aluminium disks in the firmament.

Soon as in “in two days”, she unexpectedly says. In other words, everything is quite urgent, and expectations for the show are very high. Marina Pinsky is a name in the contemporary arts scene. At 34, she has had appraised solo shows in Milan, Brussels, New York, Basel, Sydney, Berlin, and Los Angeles, has been featured at Wiels and S.M.A.K., and is already part of the collection of the MoMA in New York.

_Ivan_Put.jpg?style=W3sicmVzaXplIjp7ImZpdCI6Imluc2lkZSIsIndpZHRoIjozNTAsImhlaWdodCI6bnVsbCwid2l0aG91dEVubGFyZ2VtZW50Ijp0cnVlfX0seyJqcGVnIjp7InF1YWxpdHkiOjk1fX1d&sign=90990c3d252be1d79419699f430bcba2e218f9a9205d8b2b0a6aad9aa0b76578)

© Ivan Put

| Marina Pinsky

Behind this impressive career lie an energy for work, a sense of wonder, an urge for profundity, and a restless poetry. That restlessness is also part of her biography. Marina Pinsky was born in Moscow, moved to the Bronx when she was three, and grew up moving around a lot in the North East. After studying fine arts in Boston and Los Angeles, she came to put up her first solo show at C L E A R I N G Brussels and liked the vibe of the city. “I didn't want to live in LA anymore. I missed just walking around, normal stuff you can't really do there. And it felt really comfortable here, so I stayed. Since then, I have been dividing my time between Brussels and Berlin. I also work as a tutor at the Ateliers in Amsterdam, so I'm always doing this triangle, constantly shifting cities all the time. In that sense, it was really weird to suddenly be completely stuck in one place.”

GOLDEN HATS AND ARMY CAPTAINS

In “Four Color Theorem”, that restless spirit is given complete freedom to wander. From the streets of Koekelberg and the Hansaviertel district in Berlin in the bronze models to the stars that twinkle in the celestial maps on some of the aluminium disks. That same restlessness also stands for a particular artistic practice: an object, a fact in reality that inspires wonder and continues to tug at her until it devours her completely. “Oh yeah, big time!”, Marina Pinsky says. “When the gear starts spinning, I wouldn't be able to not make the thing. Once I start making it, it completely changes from what I had in my head. That's the exciting thing: it's also to discover how to make the work, to figure it out as I go along.”

I find it easier to sculpt in Brussels, it’s the right setting for messy stuff

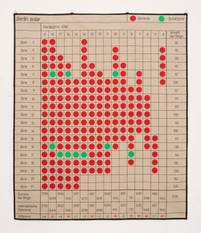

There were various hooks for “Four Color Theorem”. One was the Berlin Golden Hat, a curiosity from the late Bronze Age, that Marina Pinsky discovered in the Neues Museum in Berlin and that she multiplies in wooden objects in her exhibition, covered in four colours – referring to the “Four Color Theorem” from the title, the mathematical theorem proving that four is the minimum number of colours needed to successfully create a map. “The artefact has these decorative rings and tiny ornaments on it, that supposedly allow you to calculate time. The lunisolar calendar has been researched by the former director of the museum, but has not been deciphered completely. I really fell in love with it, because it has all this mystery behind it. Not just in terms of the calendar, but also of its provenance. Nobody understands how it was possible to make something like the Golden Hat at that time. I liked having an object full of aura but whether it's authentic or not is up in the air.”

It is that rebellious relationship between object and representation that Marina Pinsky has turned into a way of seeing and thinking since she studied fine arts, and photography in particular. Theory and practice, system and lived experience run like leitmotifs through the exhibition. And produce a wonderful sort of poetic friction.

For example, in the large central space at C L E A R I N G, you encounter seven aluminium disks. On one of them, the 1897 perspective-correcting early aerial surveillance camera made by the Austrian army captain Theodor Scheimpflug stares at you. A device that consists of one central lens and seven outer lenses, which together are capable of taking accurate aerial photographs. “When I was studying photography, I learned about the Scheimpflug effect – a technique to bring things into the foreground and the background together on the same picture plane. I was curious about who he was. And then I found out he had made this camera, the craziest thing I had ever seen.”

PAVED IN MAPS

It is anecdote that Marina Pinsky tells almost carelessly: when she visited the Bundesamt für Eich- und Vermessungswesen (the Federal Office for Metrology and Topography) in Vienna to see Scheimpflug's camera close-up, one of the employees there told her a beautiful story. “He told me that his grandfather, who had also worked there, had once brought home a whole series of lithography stones, used to print maps in the 19th century, after the mapping department had decided to get rid of them. His grandfather paved the entire garden in these map stones, and that was where he had played as a child. Eventually it made him decide to do that for the rest of his life.” Or how map and territory can inhabit the same metaphorical space.

_Ivan_Put.jpg?style=W3sicmVzaXplIjp7ImZpdCI6Imluc2lkZSIsIndpZHRoIjozNTAsImhlaWdodCI6bnVsbCwid2l0aG91dEVubGFyZ2VtZW50Ijp0cnVlfX0seyJqcGVnIjp7InF1YWxpdHkiOjk1fX1d&sign=ca7190ce4f80b1dab5fcf0fc2579f97e4b61a9685451ed6ce131cc511a06c466)

© Ivan Put

| Marina Pinsky

“At the same time, it is terrifying military technology, the ancestor of 'our' Google Street View camera. It's really weird how many different aspects of life are touched by this kind of technology,” Marina Pinsky says. “For example, the overview provided by this technology takes over too much in most modern city planning. While you also need the walkers' perspective and understanding of the city.”

A reference to that city planning is found on one of the walls in the central space, where a giant mural represents an apartment building from the Hansaviertel, a district in Berlin that was destroyed during the Second World War and was rebuilt as a social housing project, as part of the 1957 International Building Exhibition Interbau. “Though this particular building came later, it is really ugly, and does not function in the same utopian way that a lot of the original modernist buildings do. I'm pretty aware of the effect that this sort of city planning has on people, I really notice when it's working and when it's not working and I have a lot of opinions about it that I bore my friends with all the time. (Laughs) But in this time of crisis that sort of vision is extremely important. You can see that it's dangerous to live in cities the way that we are right now.”

FROM PUZZLE TO PIECES

On the opposite wall, there is a large mural of a truck carrying a large grey surface in which lines in four colours sketch an inextricable whole. An impossible map, but a territory nonetheless. The walker's perspective perhaps? All the works here syncopate with each other, play with the boundaries between object and representation, between fact and a state of metaphor, continually switching between realms in which visitors become witnesses, partake in the action, and where the central eighth camera of Scheimpflug's monstrous device is mirrored in the visitors who stand in the middle of the seven-disk circle, look up, and see what lies beneath them, in a mosaic of fields, meadows, streets, and villages. “I rephotographed Scheimpflug's photos as a way of showing the photo object as much as the map.” Objects with reflections and distortions, where trees blend into the texture of the paper. “Or this,” she gestures, “a fold in the paper. So cool!”

For a restless person like myself to make bronze models, for all eternity, of the neighbourhoods I live in, is a bit of an absurd exercise

You see and are seen. You are watched, perhaps as much inside the social block on the wall as by Google Maps. The app returns as a tool in the imposing series of models that Marina Pinsky made of the Berlin neighbourhood around her clean photo studio and of the streets of Koekelberg that encircle her dirty sculpting studio. “I find it easier to sculpt in Brussels, it's the right setting for messy stuff,” she laughs.

The models depict softly contoured buildings, rigid streets, half defined zones with holes where buildings are being torn down or put up. “There are definitely a few places where the whole system just breaks down. (Laughs) And I like that. In Mike Kelley's Educational Complex (a reconstruction of the artist's past in the form of an architectural model, red.) all of the areas he couldn't remember were represented by solid blocks. It looks like this sort of highly rational system, but it's also completely made up.”

These bronze sculptures shift between these fascinating dimensions of the rational and the made up. “I wanted to do this sort of thought experiment on Google Maps, because I really like walking around and making maps in my head. I have a pretty good sense of direction and I like getting to know places from memory. But I increasingly started to rely on Google Maps to get from place to place, and I felt that the mental mapping facility in my head was getting weaker. Through the models I wanted to try to lay both approaches on top of each other to see how it would work – tracing the map out on cardboard and then comparing the design with satellite views. That's how this big puzzle came about.”

Marina Pinsky: Four Color Theorem

“But, for a restless person like myself to make bronze models, for all eternity, of the neighbourhoods I live in is also a bit of an absurd exercise. (Laughs) In that sense, this show is kind of special. I always moved a lot in my life, but Brussels and Berlin, in this strange transitory life, are probably the longest I have ever lived somewhere. So it is stability in a way.”

Stability, or a dizzying trip that leads you from heaven to earth, from inaccessible icon (the Berlin Golden Hat) to what is all too present and precisely tries not to be (Google Maps). Along the way, thoughts about the map and the territory, the object and its representation, the system and the single soul, the social and military waft through your head. As if hiking through the galaxy, jumping from one map stone to another.

MARINA PINSKY: FOUR COLOR THEOREM

> 1/8, C L E A R I N G, www.c-l-e-a-r-i-n-g.com

Read more about: Expo , Marina Pinsky , clearing , Four Color Theorem

_Lara_Gasparotto.jpg?style=W3sianBlZyI6eyJxdWFsaXR5Ijo3NX19LHsicmVzaXplIjp7ImZpdCI6ImNvdmVyIiwid2lkdGgiOjM2MCwiaGVpZ2h0IjoyNzAsImdyYXZpdHkiOiJjZW50ZXIiLCJ3aXRob3V0RW5sYXJnZW1lbnQiOnRydWV9fV0=&sign=706842bfed08f6d1c14457023fa2c3f8488095fa5cefd36d9869b795f1bb1447)

_Raisa Vandamme.jpg?style=W3sianBlZyI6eyJxdWFsaXR5Ijo3NX19LHsicmVzaXplIjp7ImZpdCI6ImNvdmVyIiwid2lkdGgiOjM2MCwiaGVpZ2h0IjoyNzAsImdyYXZpdHkiOiJjZW50ZXIiLCJ3aXRob3V0RW5sYXJnZW1lbnQiOnRydWV9fV0=&sign=c9e9175210307769bfc59d80d1f5f3ed538c27ef90a55b0951c9af1f7efec858)

_Matthieu_Vanassche.jpg?style=W3sianBlZyI6eyJxdWFsaXR5Ijo3NX19LHsicmVzaXplIjp7ImZpdCI6ImNvdmVyIiwid2lkdGgiOjM2MCwiaGVpZ2h0IjoyNzAsImdyYXZpdHkiOiJjZW50ZXIiLCJ3aXRob3V0RW5sYXJnZW1lbnQiOnRydWV9fV0=&sign=175265b0b3f49882a1542a9be52fc6ac6dc3186113b4b0f7c578898f11a719dc)

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.