Some exemplary parks, beautiful plans and a whole catalogue of intentions. Brussels is well aware that it needs to prepare for a changing climate. However, there is still too little concrete evidence of this. "Cities come to listen to our good ideas and then implement them faster than we do."

© Bart Dewaele

| Marie Jansonpark

Want to know more about the 'Climate-proof city' dossier?

More extreme rain and especially many more heat peaks. We know what the climate has in store for us in the coming years and decades, but how can we prepare the city for it? BRUZZ visited Vienna and Copenhagen, two cities that are already way ahead of Brussels, and came back with a ton of answers. Cool oases, the sponge city, outdoor swimming or using the wind as a fan? You can read about it in our dossier 'Climate-proof City'.

On the site of the new park stood the Munthoffabriek until the 1980s. It then became a somewhat undefined space with sealed cobblestones and trees. Plans for an underground car park faded away and the current administration had the space redone after an architectural competition. Over a hundred parking spaces were quietly removed.

© Bart Dewaele

| The redesigned Marie Janson Square: the majority of the cobblestone surface was de-paved in a subtle manner. Lawns were introduced, and where necessary, cobblestones with permeable and often green joints were used.

Heavy rains and more heatwaves? The park is a great example of how to respond to it. Almost all of the existing 60 trees were retained and another 40 were added. "They are tree species that can withstand more extreme weather and that can grow bigger than the current ones," says architect Guillaume Vanneste of VVV, which drew the design together with Studio Paola Vigano. After all, trees are the best way to cool down public spaces, both via shade and evaporation.

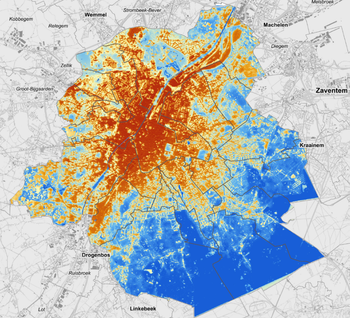

© Leefmilieu Brussel

| De rijke (groene) gemeentes Ukkel, Watermaal-Bosvoorde en Sint-Pieters-Woluwe zijn de koelste van het gewest. De gemeentes aan de kanaalzone de warmste.

What else? Most of the cobblestone surface subtly made way for a more permeable surface. On the top and sides, there are lawns which slowly turn into cobblestones with permeable green joints in the high-traffic zones. And perhaps the most striking intervention: rainwater from the newly car-free Moskoustraat is channeled into infiltration zones in the park. "During intense rain like last week, those green canals fill with 30 to 40 cm of water," Vanneste explains. "That way, we keep the rainwater here and don't burden the sewers lower down in the valley. At the same time, water cools the surroundings.”

It is an example of the sponge city principle, which Vienna and particularly Copenhagen have been using for some time. Unlike in Copenhagen, rainwater from the surrounding houses still goes into the sewers.

Paola Vigano emphasizes that the area is more than just a climate park. "A park that is only there for climate reasons makes no sense here. This should become a place where various city-dwellers feel good throughout the year."

© Bart Dewaele

| Architects Paola Viganò of Studio Paola Vigano and Guillaume Vanneste of VVV collaborated on the design of Marie Janson Square.

Concrete heat batteries

Marie Janson Park is not the only public space devoted to climate adaptation in Brussels. The pedestrian zone on Anspachlaan is quite green and rainwater flows into vegetation. In Thurn & Taxis too, forward thinking has taken place. Nevertheless, it is striking how often concrete wastelands were created in recent decades, turning into heat batteries in hot weather. Rogierplein, De Brouckèreplein or Sint-Gillisvoorplein (formerly even with more trees)? You must use a magnifying glass to find the greenery. The Molenbeek Gemeenteplein or the new plans for Koningsplein? Same. Ordinary residential streets did not become much greener in recent years either.

We are not the only ones to say so. "Although many public spaces have been renewed in recent years, few respond to the needs and challenges of climate change," wrote regional planning agency Perspective.brussels as recently as 2021. "(...) The absence of natural elements is striking."

© BRUZZ

| It's striking how often in recent decades stone deserts have emerged, which turn into heat accumulators during hot weather. Rogier Square, De Brouckère Square (pictured), or Saint-Gilles Square? Greenery is often hard to find there, as if you're searching for it with a magnifying glass.

That additional urban green space is nonetheless much needed in times of climate change. If it is constructed like the urban sponge we were just talking about, greenery can help to mitigate the effects of extreme rainfall. Heavy rainfall today does not only lead to flooded basements and tunnels of the Kleine Ring, it also caused sewers to overflow eighty times in the Zenne (and nineteen times in the canal) last year. "Every time, this means a bomb of microplastics and often fish deaths," according to Pieter Elsen of vzw Canal it Up. "Furthermore, Brussels has not set itself a deadline to resolve this, as other cities have done."

But by far the most pressing issue in Brussels is the heat stress caused by the changing climate, resulting in more and more heat deaths. A glance at the Brussels heat map already shows how the downtown area and working-class neighbourhoods are getting much hotter than the greener areas of the second crown.

The Canal Zone takes the crown in this regard. Residents there already suffer two to three times as many heatwave days as those in the green periphery. Especially in the evening, when the stone city continues to release stored heat, the contrast with the surrounding countryside is stark and can reach 10 °C. It’s the urban heat island effect, you know. "It's those nights that can be deadly for vulnerable inhabitants," says Simon De Muynck, researcher at ULB and coordinator of the Centre d'écologie urbaine.

© Lieven Soete

| The canal zone in Sint-Jans-Molenbeek, as seen from the rooftop terrace of the Brunfaut Tower during renovation: very little greenery, lots of pavement, and the hottest zone in Brussels.

Meanwhile, summers also continue to get hotter. The KMI expects the Brussels city centre to have to deal with heatwaves three times as often over the course of the century. Those heat periods will also double in intensity - in the most pessimistic, but also most likely scenario.

The heat map thus shows how the warming city is also a social issue. Because the most affected areas are also usually the poorest in the region. And that is not all. Those who are poor and live in such a heat-affected zone also have a harder time than a wealthier neighbour. Taking shelter on the ground floor? Ventilating at night between the front and back facade? Or getting away to a country house? Tricky when you live in a small flat and have limited resources.

"In general, we may know these mechanisms, yet we continue to severely underestimate them," De Muynck believes. "We have also only just started to do a finer analysis of the risks per municipality. How many people actually die from heat and how is that linked to the socio-economic situation? We don't know that, or it is barely studied."

Municipal fragmentation

A major obstacle here is the approach per municipality, notes De Muynck. "The regional strategy in terms of climate adaptation (part of the Air Climate Energy Plan) has to be translated into municipal action plans, but different municipalities approach this very differently. Ukkel, for example, has involved students for this purpose.

De Muynck therefore advocates more regional coordination and a kind of CurieuzenAir for temperatures. " Once we really realise how big the differences are, the urgency will also begin to sink in more," he says.

"If you really want to act for the climate, you should have millions to spend on it."

The researcher believes this sense of urgency will be needed to release the necessary funds as well. "If you really want to do something for the climate, you need to be able to spend millions on it, and municipalities today have no idea where to find that kind of money."

We also check in with Brussels master builder Kristiaan Borret. How well are we doing in terms of climate adaptation? "In terms of public space, we are in the middle of the pack, at least in terms of intention. The problem is that in Brussels things often stall when it comes to implementation. Some foreign delegations pick up ideas here that they then implement faster than we do. For example, Oslo visited the pedestrian area on Anspachlaan and was more consistent than Brussels in making the city centre car-free.

What does less space for cars have to do with climate adaptation? "Those cooling trees have to be somewhere," Borret explains. "In Marie Janson Park, which I think is very successful, the greenery is now partly where parking spaces were."

This struggle to limit the car’s place is an issue that Vienna and Copenhagen also wrestled with, we noticed on our climate trip. It is also still in full swing in Brussels, and not only in the context of mobility plan Good Move, notes the master builder. "In the new regional urban planning regulation (Good Living), we want to stipulate that a maximum of 50 per cent of public roads can still be used for private cars. But this is meeting resistance from municipalities and some political parties."

Trees in every street.

The master builder attaches particular importance to interventions on the level of the ordinary street, which must then be done on a large scale. "A large forest has much less effect than greenery in every street, where you can then combine it with water-permeable parking spaces. And things are not moving fast on this front. That even applies to a municipality like the City of Brussels, with a tree plan and the intention to put a tree everywhere possible. You would then expect to see a massive number of trees popping up in the streetscape by now, wouldn't you?"

How many new trees will the Region and the municipalities actually plant? 25,000 in Vienna during this legislature, in Paris even 170,000. Both the City of Brussels and the Region lack such a highly numbered ambition. "Europe is pushing for this," admits Pascale van der Plancke, who coordinates regional policy on climate adaptation at Leefmilieu Brussel. "But at the moment, we don't even really know how many trees we already have; we are counting them now." Nor does van der Plancke think the number of trees is all that matters. "Often it is more important to plant specimens with large crowns in the right places."

Alain Maron (Ecolo), Brussels Minister for Climate Transition and Environment, says that the development of the green and blue (water) network is more important than a tree figure. He points to a whole series of new green spaces which have come into being in recent years, but acknowledges that things sometimes move slowly, mainly due to local opposition, such as with the swimming pond in Neerpede.

A cooling public space with lots of greenery: it is a necessity, but it is not enough. We noticed this particularly in Vienna at 36°C. In an ideal world, people could stay in their own cool homes in such heat. Proper insulation and an exterior sunshade already keep out a lot of heat. And those who have a heat pump with geothermal energy can also use it for climate-friendly cooling. But it is very difficult and expensive to apply that principle throughout the city, especially in a city with small-scale housing like Brussels.

© Delphine Frantzen

| The de Brouckèresquare revisited.

A lot of cities are therefore working on a network of cooling shelters for heatwaves in buildings. In Barcelona, meanwhile, there are already over two hundred of these public places. In Brussels, there is no such initiative yet.

In short, there is still work to be done in Brussels. And there is also hope, we think in Marie Janson Park, in a pleasant 31 °C in the shade of a maple tree. Architect Vigano looks around approvingly. "This park wants to be a reason to keep living in the city." When we talk to the master builder on the phone a little later, we hear echoes of that optimism. "When I walk through that new park, I think: cities will survive climate change," he says.

Read more about: Brussel , Milieu , Gezondheid , Klimaatbestendige stad , klimaatverandering

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.