The second and last edition of the arts festival Border Buda, entitled The Woman Who Thought She Was a Planet, draws a line under the artistic project which will put the Buda district in northern Brussels back on the map. Not as a desolate no-man's-land in desperate need of development, but as a vibrant place full of history that should be valued properly.

©

Heleen Rodiers

| Border Buda-curator Els Silvrants-Barclay

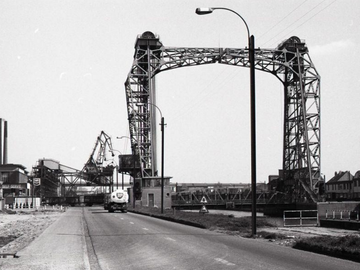

Three years ago, Border Buda launched a plan to change people's perception of the Buda district, on the borders of Vilvoorde, Brussels, and Machelen. Buda now often evokes thoughts of faded industrial glory, heavy traffic, and overgrown wasteland. With the viaduct grimly looming above it all.

“Most see it as a dirty and abandoned place,” says Els Silvrants-Barclay, curator of the concluding edition of the Border Buda arts festival. “Yet it's a district full of life, though much of it is hidden behind expressionless façades. Buda is Brussels' back office, with essential services increasingly being pushed out of the city. Think of caterers, plumbers, and removal firms, but also Turkish banqueting halls. Some people living here, often in alternative living spaces, would struggle to find housing elsewhere. And nature has frequently been given free rein, with water playing a key role in this former marshland.”

"Buda is Brussels' back office, with essential services increasingly being pushed out of the city"

Curator Border Buda

With The Woman Who Thought She Was a Planet, Silvrants-Barclay also wants to look beyond Buda, challenge the dominant development logic, and explore diverse future scenarios for such urban spaces. “Artists are often deployed to enhance such transitional spaces in a non-committal way, after which residential towers and cappuccino cafés for the middle classes are planted. But we aspire to have a more authentic impact, by encouraging a different way of looking and testing new things together with who and what is already there.”

From an even broader perspective, the commercialisation of land will be critically examined. “We no longer have an emotional relationship with land, while it literally gives us ground beneath our feet, it carries us. We invite artists to imagine a different kind of relationship with land and to think about landscapes as living bodies.”

Steel ghost town

Unlike the first edition, the festival doesn't offer a walking exhibition this time. The action takes place mainly across four locations in the historic heart of Buda: an open field between businesses, the factory building of the former Fonderies Bruxelloises (Fobrux), café The Corner, and cultural hub Buda BXL. “This gives visitors time to properly absorb these special places and discover their hidden aspects. We invite people to slow down and truly spend time in Buda.”

The programme includes installations, screenings, performances, and concerts. In the open field, the Agency collective will tackle ideas around land ownership through a performance, with the central question of whether a landscape can be a work of art and if nature can have “copyright”. Japanese sound artist Tomoko Hojo will present a musical piece based on sounds recorded at a former pond in that field – such as insects – and ask the audience to add an extra dimension with their voices.

Artist Sarah Smolders has created the sculptural installation Time, Set in Stone, in which a stone is polished by the water of a mill – a reference to Buda's former stonecutters and the abundant presence of water in the area. Jota Mombaça references that fluid and unstable foundation by soaking cloths in water so they absorb various residues, and then drying them in such a way that the ghosts from the past become visible. That work, called Ghosts, will be exhibited in the Fobrux building.

In café The Corner, Lucile Desamory and Carola Caggiano's group TRANSPORT will present a musical ode to friches or transitional spaces. The song “Fleur de Buda” from 1971, in which Antwerp singer Della Bosiers describes the neighbourhood as a “steel ghost town”, will surely be featured.

The significance of Buda

“Actually, the entire festival is an ode to the friche and a plea to preserve it,” says Silvrants-Barclay. “Without misplaced romanticism for the precarious conditions in which some people must survive, of course. But people so often talk about the need for inclusive urban areas and wild nature without seeing that this already exists in places like Buda. 'The wasteland is the future,' that's our message.”

Besides the present and the future, the Buda wasteland is also an area with a rich past. Under the banner “Het Be(h)lang van Buda” (“The significance of Buda”), the district's heritage has been documented by local groups over the past three years. Among other things, the Radio Fantôme project brings that history back to life with oral testimonies. Among the conjured ghosts are many lost businesses: during the second industrial revolution, Buda was bustling with activity, with manufacturers of screws and bolts, dyes, wallpaper, stoves, tractors and French family cars.

“But even now, very few buildings are actually empty,” emphasises Silvrants-Barclay. An important example is the old Fonderies Bruxelloises, where cast-iron kitchen appliances were made until the 1970s. After the festival, a closing event will take place there in September. Architects Laura Muyldermans and Bart Decroos have researched the biography of the former factory, and on that basis, a proposal will be made about the future of the building.

“Just as with the development of neighbourhoods, the repurposing of buildings usually doesn't take into account the many unknown aspects of the past,” says Silvrants-Barclay. “We give a voice to the diverse ghosts of this magnificent building, and let them help decide its future.”

The Woman Who Thought She Was a Planet, the second edition of the Border Buda arts festival, will run from 20 to 22/6, borderbuda.be

Read more about: Haren , Events & Festivals , Border Buda , Buda , Els Silvrants-Barclay , wasteland